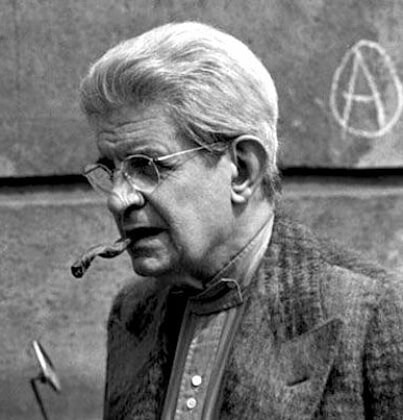

Derrida.

“It speaks in the second person.”

“I am walking on ground that is forever giving way. ”

“Friendship was [Derrida’s] first criterion of choice. ”

This is a paraphrastic second-person account [YOU] of reading the Derrida biography by Benoît Peeters (2011). Through an alternating exercise of reading, memorising, forgetting, rewinding & daydreaming, I expand beyond the confines of the book's 500 pages+ to allow 20 years of reading Derrida infuse the text by way of speculative addresses to Derrida towards a middle-ground, where biography & theory/ writer & reader/ life, death & writing meet, challenging, to an awkward & always inadequate degree, Derrida's claim: "I am one thing, my writings are another." [This text was first posted inchmeal on Instagram over the course of a month, September-October 2020, in the lead up to the American presidential election.]

SOMEWHERE between adolescence & old age; between Aristotle, Nietzsche, & Heiddegger; between Jean Jacques Rousseau (whom Nietzsche was a fervent critic) & André Gide (whom you may have crossed paths with in your native Algeria), you came to the conclusion that the philosopher's biography was best described in one sentence: “He was born, he taught & he died.” So without further ado….. You experienced up to the age of thirteen, being a Shepardic Jew—a minority within a minority—in Algiers under a Vichy France, the nature of being a younger brother, being the first in your class, being without school, being a best friend, being platonic with girls you loved, living with deaths in your family, anti-semitism, prejudice, gunfire & bombing, inequality, sadness, dislocation, books, cinema, football, all in a local world blistering hot & concrete. You were no victim or traumatised wallower or repeater in your future philosophy, no matter how persecuted your young life up to then had been. You placed yourself in relative heaven to the hell of the European Jews: silence & distance your knight's move. You felt sorry for your father, whose menial & minimal job kept him strapped into his car while traversing beautiful Algeria from sunrise to sunset which, as a rare passenger, you experienced a few times & were glad of & revisited in later life. Following your countryman, Albert Camus, you fetishised the football boot for years as a recourse to being expelled from school for being “a little black and very Arab Jew”. Under de Gaulle's France & the abolishment of the Vichy laws, you returned to school with your siblings, where you maneuvered from one course to another, one philosopher to another, until you settled on the pathos of Heidegger & political “commitment” of Sartre, whose impact upon you was complete, until you found your voice in the written word.

Derrida, 19, Paris

YOU ended up boarding in Paris in a post-secondary school to prepare for the exam for entrance to the École Normale Supérieure (ENS). You wore a grey smock. Your Jewishness was nothing special; your sexual experience courtesy of the Algerian brothel you frequented was. Your grades were above average, ‘potentially’ better in the eyes of your teachers. Your summers were boring (you got shamefully fat). You had a nervous breakdown. You missed your friend, who received your letters, almost love letters that are devastatingly sentimental & self-defeating. You received a comment, the first of many from teachers & peers, friends & enemies, that advised you to “accept the rules and not invent”. You failed your exams. You repeated. You passed. Due to disinterest from your teachers, you took on Heidegger yourself in the few French translations that existed in the late 1940s. After passing the final exam to take your place in the ENS (where you would also receive a teacher's salary) you write a letter to one of your most unteacher-like teachers to thank him for his criticism & rigour. Although you still write to him, you began to drift away from your best friend Michel Monory, the reasons... distance & different paths taken? (There is something exaggerated in terms of the intimacy & vulnerability shared in those letters you write to Michel Monory, as if the letter, the word, language itself, gave you permission to be intimate & vulnerable, whereas the lifeworld pushed you back at a safe & critical distance.) You met the social world asymmetrically. One of your final trips to Algeria, before you took up your place at the ENS was, you felt, a wasted summer without writing or reading; just a whole lot of nothing in the heat & fatigue & inability to reconnect with old friends & old habits. Friends from the Lycee (state secondary school) in Paris visited you at home, & you entertained as long as you could bear it, but soon sent them on their way. Your ambitions in your homeland were harboured by a temperament that was annui & without ambition. You wished to be in the grey & wet & dirty of Paris again.

Louis Althusser

BACK in Paris at the ENS, as a paid student, you bought books, went to the cinema & enjoyed the Latin quarter. Politics & friendship became the overriding themes of your first year there, made manifest in the published & public quarrel between Sartre & Camus, once friends, now enemies, after the publication of Camus' The Rebel. This spirit of fighting among friends was compounded further by Sartre & Merleau Ponty's intellectual & political breakup over their political diametric deviations in terms of Communism, America & the USSR, & the different languages therein used to reconcile the political question in a philosophical arena. At ENS you met an unknown & charismatic Michel Foucault, four years your elder, & 34-year-old Louis Althusser, more than a decade from his legendary status. You were surrounded by a little known world, intellectually potent & politically divided that would explode into what we know today as French Thought. You wrote an essay on Husserl, which Foucault or Althusser did not offer to read; an essay that Jean-Luc Nancy would read later & fail to identify a “young Derrida”—Derrida is “already there, fully armed & helmeted like Athena. However, it's evident what he lacks—a certain youth, with its playfulness.” Your playfulness did venture into your social life when you first flirted with a relationship that would last a lifetime with Marguerite, your future wife. Concurrent but violently diametric to this burgeoning love affair, a racially divided Algeria under French colonial rule fell into an eight-year war. Althusser, a fellow Algerian, would become very close to you as a teacher & friend over the next two years at the ENS. He would read your essays & give you feedback that would help you to appease the expectations (rather than your diverging ambitions) of the examiners in terms of the subject aims & outcomes for the final exams. The examiners would not recognize themselves in your remarks on Husserl & Heiddegger. This relationship you had with Althusser would be broken on & off due to the deep depression that assaulted Althusser sporadically then & for the rest of his life. Reading your last letter of thanks to Althusser after you passed your exams with a mediocre grade, it shows you felt & privately shared the same criticisms regarding the ENS. Althusser advised you to “Chase this unpleasant reminiscence, and the faces of your judges, from your life and memory as fast as you can!”

Derrida, 20, Prague (Marguerite's Family)

YOU received a bursary to study in America at Harvard. You took it with trepidation—Marguerite by your side. Everything in America was “on the surface”. You still wrote to your best friend Michel Monory. Sentimental, melancholic & intimate as ever, the letter, or Michel himself, disembodied & distant, had become a vessel or vehicle through which you could spill emotion in a long & repetitive vernacular that you would explore further in your autobiographical text ‘Circumfession’. Michel Monory, now in Algeria, sent you a letter that describes an image from the frontline of a naked Arab boy, hanging from a door from his wrists with the marks of the “most sophisticated tortures”. Far from the frontline, you visited big libraries, bigger than in Paris. You read Husserl—building slowly towards your translation of his best work The Origin of Geometry, while also reading Joyce's Ulysses & Finnegan's Wake which you felt "the most grandiose attempt ever to bring together in one oeuvre ‘the potential memory of mankind’.” You read & write English better than you speak it. You write to Althusser, sharing your experiences of American philosophy, which you opined “poor”, “elementary” & “innocent” but enthusiastic & youthful. Whereas the Sorbonne “is an old worm-eaten house through which the spirit blows in hurricanes”. You married Marguerite in America before your returned to Eurpope & the criticisms your family held in respect to marrying a woman outside of your milieu. You return home to avoid full military service in Algeria due to your father securing a job for you teaching the children of soldiers at a military outpost outside Algiers. Although you didn't experience the battlefield first hand, this did not preclude you & Marguerite from experiencing the political & psychological tensions that pervaded the militant, fascist rhetoric & forced silences that were necessary to evade inviting violence unto yourself, your loved ones & friends. As French power changed hands & de Gaulle assumed power once again, whom you supported in terms of his policies that went towards a less racially divided Algeria, even if that meant, as an anti-colonialist, French rule.

THE possibility of a teaching job at the Sorbonne University in Paris—helped by Althusser & the director of the École Normale Supérieure, Jean Hyppolite—is deferred due to an appointment at a secondary school in the sleepy town of Le Mans, which you are forced to take due to a bureaucratic power play by the secondary school authorities. Although meticulous in your lesson preparation, your Le Mans students are not so meticulous. You drown your book shelves in linseed-oil in your big Le Mans apartment & your books stay greasy for months. Your letters are emotionally flat before you fall into a deep depression, the worst of your life. Your teaching position at the Sorbonne comes back into play as red tape turns pink under the levelling light of time if not exactly hope or happiness. You take antidepressants, new to the market in '59. They work, with side-effects—tremors & such. As an assistant philosophy teacher at the Sorbonne you have free reign in terms of syllabus & subject. This is your first & favourite time in higher education in France. Gossip surrounding your lectures travels quickly, resulting in up to 150 students piling into your classroom. Students find you socially shy & physically clumsy, but brilliant, approachable & generous with your time.

DURING this time Algeria is still to the forefront of your thoughts, even though you kept publicly silent & critically ambivalent during this period (& for decades after), as was the way of your philosophical approach (Aporia) when it came to the binaries of argumentation & hierarchy in a human world where “Logocentrism” (a faith in language, especially speech, to get to the truth of the matter) is inflated, dangerous & reductive. A book published by your old classmate, Pierre Nora, provokes you to express yourself on Algeria in a typed letter that thanks your friend for writing such a difficult book, but also criticises him for placing most of the blame on French Algerians, an identity that you claim as your own. You also defend the nuanced position of Camus in such a politically & socially complex situation. Your biographer is of the mind that, like Camus, you wished for a “French-Muslim Algeria”? During this time you also finished the translation & introduction to Husserl's Origin of Geometry to the great praise of Hyppolite & warm regards of Paul Riceur, whom you desired acknowledgement & affirmation from most of all & partly got, even though you believe, after meeting him for dinner, he did not read you as closely as you would have read him? You turn to Althusser who is your best & most affirmative reader. Algeria then comes to metropolitan France in the form of the Paris bombings of 1962, signalling eminent Algerian independence, meaning French Algerians are forced to choose between “the suitcase or the coffin”. You dash to Algiers to help you family pack their suitcases, declaring later in the political turn of your philosophy, that even though you wanted Algerian independence, you wished an alternative, or at least “different problematic” to outright sovereignty of states, like Israel &/or Palestine; and wished the French Algerians could have stayed in Algeria which they wanted. Forget Islam, Christianity, Judaism, Algeria was above all, your & your family's home.

Michel Foucault

YOU change your name from “Jackie” to “Jacques” for your first publication The Origin of Geometry, writing later, “I must have erased more things than I could say in a few words”. Your lengthy introduction (170 pages) to your translation of Husserl's Origin (43 pages) was the original style that you sought & confessed you were seeking in a letter to Michel Foucault. Your style's signature involves taking a piece of writing & assiduously, determinedly & critically unpacking & unpicking the navel of its argument so a new reading & text is born. You would continue in this deconstructive vein in terms of your article writing for the prestigious avant-garde journals Critique & R[evue] de M[etaphysique], where you would continue to flatter & critique your living & local peers. A letter to Emmauel Levinas before the publication of your article on Levinas' corpus shows how intimacy & critique go hand in hand in your method, admitting to being “as close to your thought and as far from it as possible to be”. It seems your energy to write comes from finding the gaps between a proposition, an argument, a sentence, a word, a letter, towards an atomisation of language, beneath language itself, which failed in some way to hook itself onto the world; you disembowel language so the skin of language is left torn to reveal its slippery organs. It was with a feather & scalpel in hand that you presented your first major paper at the prestigious College Philosophique in 1963 on the subject of Foucault's History of Madness, from which you surgically removed three pages of text to proceed to undermine the “book's postulates, including the very definition of madness”. You did write in a letter to Foucault a year earlier that History of Madness had given you a desire to write “something like a paean to reason that would be faithful to your book”. Just like you to invoke sanity in the face of madness. Foucault received the critique positively, thanking you “for the immense & marvellous attention you gave to my words”. However, your biographer hints that your “friendly relations” would deteriorate nine years later in a “violent polemic”.

FOLLOWING some political & bureaucratic side-stepping after your contract as assistant at the Sorbonne lapsed, you took a position at the École Normale Supérieure, your previous haunt, at the behest of Althusser, whose dependence on you to get students through the exams evolved as his psychological health fluctuated. You entered ENS at a time when a new political & theoretical storm was brewing under the classroom floorboards in the name of Marxism propagated by a healthy Althusser (a prominent member of the Communist Party) & acolytes (including a young Jacques Rancière). Everything seemed to be in flux for you after the steady climb of your reputation. ENS housed Jacques Lacan's now famous seminars Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis & Althusser's now famous Reading Capital, which seemed to shift the focus away from your philosophical concerns. The “theoretical intimidation” of Althusser's Marxism & the “bourgeois science” of Lacan's psychoanalysis was a world apart from the phenomenological foundations of your approach, which in contrast to the lively discourse of Althusser & Lacan, was deemed "backward" or “idealistic”. Things were more politically charged & dogmatic under the “Shadow of Althusser”. Somehow, you & your peers were able to compartmentalise the philosophical, pedagogical & political so the day-to-day running of a school could be sustained.

Jean Genet

YOUR biographer keeps referring to your fragility during this period, threading letter fragments into the narrative from your heavy correspondence with peers & friends that highlight your need for support for your philosophical project during a time when your writings are growing in readership & reputation. Before his rise to legendary status, Althusser writes you a thank-you letter during a mental breakdown, acknowledging the sacrifices you have made in his absence to keep the students on track toward their final exams; & in witnessing Althusser's breakdown you may have revisited your personal breakdowns, that being the biggest sacrifice of all. At this time you write a long article on the under-appreciated Antonin Artaud. Like previous articles it creates a stir among those that have a vested interest in the subject matter, as if under your pen the subject is exorcised from the husk of history into the present as an object that rattles the world awake. You meet Jean Genet for the first time, whom a friend describes as a contemporary Artaud. You form an unlikely & lasting friendship with Genet. In 1965 you write ‘Writing before the letter’: “a sketch of the first part of the book Of Grammatology… the matrix that would govern the rest of [your] work”, & where the term deconstruction—“bound up in the mechanical”—would become yours like a name given at birth, discovered in the French dictionary as,

1., To disassemble the parts of a whole. Deconstruct a machine so as to transport it elsewhere.

2., Grammatical term. To carry out a deconstruction. To deconstruct lines of poetry, suppressing merely so as to make them similar in prose. [...]

3.To deconstruct oneself. To lose one's structure. "Modern erudition attests that, in a region of the ancient Orient, a language that has reached its perfection, had deconstructed and deformed itself by the sole law of change, a law natural to the human mind.

Jacques Lacan

YOUR article ‘Writing before the letter’ gained praise from those who mattered, Foucault & Levinas among them. You followed this up with an article on Freud which Roland Barthes reacted to, “More and more, where would we be without you.” In these articles you placed a particular emphasis or privilege on the act of writing over speech, which was an inversion of how philosophers like Rousseau saw it, writing being, to his mind, a corruption of the wholeness & naturalness of speech. So why then, if speech was so whole & natural, why did we need writing? This privilege you stress on writing is not to say that writing comes before speech in your project, but to balance the scales between the Western privilege of speech over writing. Once again, you are suspicious of the hierarchical nature of binaries, good vs evil, light vs dark, white vs black and so on. The following year you have a series of run-ins with Jacques Lacan that would prevent any relationship from forming that wasn't antagonistic. First, Lacan recounted a private anecdote you shared with him concerning your wife & child in a lecture without permission; then he signed a copy of his Écrits with a dedication, which read, “To Jacques Derrida, this homage, which he can take however he pleases.”

YOUR spat with Lacan began months earlier at what would become the famous Baltimore conference at John Hopkins University, where Lacan, Barthes, Hyppolite & yourself were presenting. Relayed by your biographer through witness account & anecdote, you addressed Lacan with a question at a conference dinner. Lacan replied with some paradoxical remark & added, “You [Derrida] can't bear my already having said what you want to say.” It was a dig. You took it as such. Lacan would take to the stage in Baltimore & fumble dreadfully, switching from his inadequate English to French midstream to the dismay of the organisers who thought it “a bad joke”; whereas your paper ‘Structure, sign and play in the human sciences’ would put in to question the very foundations of structuralism under Claude Lévi-Strauss before structuralism was fully discovered in America. As your biographer summarises, you were breaking away from “the ethic of presence”, “the nostalgia for origins”, “freed from the tyranny of the centre”, all of which affirmed “play” as a priority. Some of your closest colleagues were mesmerized but confused as to where you were going. You replied that that was the point, to destabilise the very foundations of Western philosophy, which you would.

Gabriel Bounoure's copy of Writing & Difference

YOUR biographer is generous in his weaving of your letter correspondence with peers, making this an accidental autobiography of sorts; whereas his necessary narrative, moving from A to Z in the chronology of your life, is merely signposting; & his confrontation with your philosophy appropriately suggestive, especially considering how your philosophical project sometimes, most of the time, loses the reader in what Geoffrey Bennington describes as flashes of insight that can also blind the one who discovers them. You are particularly intimate & vulnerable with one Gabriel Bounoure, in whom's judgement you invest great importance, like a father figure, being 44 years your senior. Nevertheless, 1967 is “A Lucky Year” according to your biographer's chapter title: the birth of your second child, Jean-Louis-Emmanuel (named after your closest peers, Genet, Althusser & Levinas respectively); an invitation to Critique's editorial board alongside Barthes & Foucault; the publication of three major works, Writing and Difference, Speech & Phenomena, & Of Grammatology, the latter submitted as part of your PhD Viva, & which, through their own admission, none of the examiners had managed to read. Even armed with such seminal texts, your Viva defence was a “one-armed welcome, the session… an act of war--bitter, raging--in which all the current tensions weighed down on the debate, with the exception of the text”.

Tel Quel (avant-garde magazine) with Phillipe Sollers & Julia Kristeva centre

Intellectual skirmishes seemed to be part of your "Lucky Year". You would get entangled with your long-time friend & publisher Phillipe Sollers of journal Tel Quel & Julia Kristeva, the rising intellectual star only months after alighting with a theoretical thump on the French scene on a plane from Bulgaria. The reason: you shared an offprint of Kristeva's article before it was published in Tel Quel. Later you would discover that your friend Sollers' somewhat exaggerated reaction to sharing Kristeva's article prematurely, which was part of the peer culture, stemmed from being in love & secretly married to Kristeva. And then there was Claude Lévi-Strauss, merely an “ethnographer in the field” in his “casual use of philosophy”, who felt, under your dissecting knife, irritated by his texts' unsuitability for your cuts. And then there was your classmate Gerard Granel, who dealt Foucault a critical blow in an article for Critique, which had your name in the title: ‘Jacques Derrida and the erasure of origin’. Your fellow board member Foucault wanted you to “oppose” one “extremely brutal paragraph” in the article, conveniently forgetting his own “self-imposed rule” that stated in no uncertain terms to “not to intervene, either for or against, on any article concerning [him]”. Of your three publications that year, Of Grammatology would be the most famous, even though some, yourself included, place Speech and Phenomena top.

YOUR text that coils arabesque through the French institutions & beyond—America, Germany—puts a strain on your relationships within the close knit & “definite, specialised” readership in the Parisian scene, represented by editors & writers who supported you in the early years but who are now becoming worn down by a saturation of the Derridean. You can imagine & understand how such visibility, underscored by a particular negativity in terms of your deconstructive & differential processes, would affect such a small & competitive community (academics!), as you chipped away inchmeal on their goodwill as the defended & deferred to your cellular-scale search for the signs of an-already-there deconstruction (as if in remission), deep down in the texture of the text. As you wrote in a letter over a decade earlier: “I am no good for anything except taking the world apart and putting it back together again, and I manage the latter less and less frequently.” Letter to Michel Monory, 1956.

Derrida, photo booth, 1970s

YOUR biographer evades getting bogged down in your theories, instead making efforts to simplify with blocks of quotations which are your most “famous” lines. Uncannily, those blocks become even denser as they are orphaned from their beginnings & endings, hemmed by a text of another kind, a biographical kind. These extracts of text are supplemented by images of you as potentially—that pedagogical term of condescension—handsome but “dressed rather drably, like a traditional philosopher… ill at ease in social situations. Only gradually did he free himself up, inventing a public persona for himself and a form of erotic identity that he made his own” (Sam Weber, Berlin). The image of your text, the image of you, & the image of your principled resolve in terms of race & politics is coloured by anecdotes, such as when you pulled out of a colleague's conference after hearing that the same colleague had made anti-semitic remarks, & confronted him head on for doing so, which he denied. Years earlier, after being invited to a dinner party by a university friend, one of the guests made an anti-semitic ‘joke’ to the laughter of the room, whom you called out, out loud, to the embarrassment of everyone present. You also partook, like everyone else, in the spontaneous May 1968 protests, but at the time were suspicious of the “spontaneism” of this social & cultural revolution. Nonetheless this was a time when there was an ideological shift in your cultural & social surroundings, but also in your writing, which was becoming more literary, like your letter writing, private & public bleeding into each other—an artery had been opened. You continued to write articles. One article, inspired by your less-close friend & Tel Quel editor Peter Sollers' novel Numbers, was “nearly as long as the fiction”, which gave Sollers “the [ambivalent] feeling of ‘a carnivorous osmosis’”. There is a tendency to your intimate & platonic relationships that swerve off-road under your intense drive to meet them the whole way. Too much?

Foucault & Sartre protest

POST-MAY '68, with a new political agenda stressing the need for a new education system, you are invited to propose & develop a new experimental school in the forest of Vincennes. You take care of the development of the philosophy department & introduce the notion of psychoanalysis, not taught in any school. These administrational duties, necessary duties, take their toll: a permanent teaching position is always out of reach in France. America comes calling in the form of John Hopkins University. Philosopher Paul de Man, of German origin (& other secret origins soon to be unmasked) is reading you closely alongside his students at Cornell University. You must have put some effort into that visit in '68 because the legacy of testament & anecdote left there sealed your future influence on American institutions whether as a friend or an enemy of philosophy. At home in France, May '68, a social & cultural revolution, has repercussions for the old generation of philosophers & philosophy as a taught subject. Further, your most intimate friend, Gabriel Bounoure passes away in '69.

AT this point of reading your biography (200 pages in) you might like to know that your biographer takes great pains to erase his presence from the text amidst scattershot extracts & traces from your public books & private correspondence. Like your immense introduction to Husserl or “carnivorous osmosis” of Sollers, the biography is more you than the biographer's. Knowing your feelings about biography outlined succinctly in the documentary that was made about you just before your death, this reader wonders what you might think of such a biography, almost removed of the fantasies & fiction & baggage of its biographer? Of course, the biographer has selected & edited your interviews, letters & text to collage a narrative that is his, emphasizing pivotal moments that keep the reader dramatically adrift in the waters—never still—of your thought & life. That said, there are moments included here, chapters even, that are quite everyday, boring even, wherein one fails to paraphrase or remember, but somehow through reading, they resurface later as eyes & words trickle down the page.

Philippe Sollers, photobooth

YOUR biographer titles Chapter 6 ‘Uncomfortable Positions’, as if there were none before now. You seem to haunt those writers you have reviewed. Geoffrey Bennington does this thing in a presentation on one of your most difficult passages in one of your most difficult books, Of Grammatology, wherein animated letters from A-Z fade in and out of focus as if language written is never fully exorcised like the litters on the gravestone of a loved one. Jean-Joseph Goux, “a young scholar who [you] admired” wrote in response to your article on Sollers' novel that he “must have read [your] immense article on Numbers as an attempt at appropriation”. Is that what you were doing? Appropriation? That said, is not all text after the fact, after Homer, an appropriation, mimesis, imitatio, influence? Unless you don't believe in the integrity of philosophical foundations á la the neo-pragmatist Richard Rorty: Did you read him? His emergence in America ran concurrent with yours. He read you, closely. Reading your private correspondence with Sollers you continued to share your obsession with his book; but this obsession, reading between the lines & changing tone of your letters, had transformed from one of all-out praise to a latent questioning & struggle with his new book & perhaps Sollers himself, as the distance between you & he became greater? After Lacan had out-stayed his welcome at the École Normale Supérieure with his flash car & cigarettes that created a plume of what some deemed (not you) nothing more than smoke & funhouse mirrors, Sollers grew closer to an “isolated” Lacan, alongside Kristeva, who was becoming, some say, your main theoretical rival?

Bernard-Henri Levy, ‘70s

A young Bernard-Henri Lévy, the media image-conscious & charismatic poster boy for the future Nouveaux Philosophes, is also mentioned among those who sparked “Uncomfortable Positions”. Lévy enters the École Normale Supérieure in '68. Your biographer shares a parodic extract from Lévy's Comedy, which colourfully describes your first meeting, portraying Lévy as the intimidated & awestruck student, & you, the great Derrida, a surprisingly normal lecturer in both dress & address. Through '69-'71 you would form new friendships with Jean-Luc Nancy & Sarah Kofman, & new enemies when Jean-Pierre Faye, your former editor of advant-garde journal Critique, whom you had distanced yourself from, suggested an undercurrent of Nazi ideology in an article based on the fragmentary nature of Of Grammatology. Your biographer writes that you “abstained from reaction”, as you would remain silent & aloof on taking a position amid the political ferment smouldering in the left-right, youth/elder, Communist/Maoist fractional politics that possessed French intellectual circles since '68. Your political stance, even though to-the-left, would always be ambivalent, like the oscillation of the pendulum swing of your philosophical method which never took sides but hovered between extremes, an uncanny centre, which for some was moral relativism, leaving your philosophy open to aggressive slurs like Nazi ideology. Earlier on your biographer wrote something about you as a child staying silent after an argument broke out in your home with a family member, maybe your older brother René. Was silence your refuge from emotion as well as language?

“Then came the beginning of the academic year. The master received, in private, the new students in that office in the rue d’Ulm of which we had all dreamed. There he was. In flesh and bones. Younger than I had imagined. Pleasanter, too. Almost friendly. Good heavens! The philosopher, the giant, the pitiless deconstructor, the mysterious writer of whom I could never have guessed that he had a doctrine on such trivial questions as a ‘thesis outline’, a ‘topic for a Masters’, a ‘syllabus for a licence or for the agregation’ - could it be him, that immense personality, that travelling companion of Tel Quel, that artist, just like, quite simply, taking the time to welcome his new pupils and talking to them in a language that was the same as that of all normal professors? Yes. It was indeed him. I could weep at the thought. I was so moved that I was speechless. ‘Who are you? What do you do? Are you a Germanist? A Hellenist? A Kantian or Nietzschean? A dialectician a la Hegel or a la Plato? An idea, in a word? A concept?’”

AMERICA, & perhaps its distance from Parisian institutional politics, seemed to give you, like James Joyce, a perspective & feeling of protection when you did that interview for the editors of Promesse (Jean-Louis Houdebine & Guy Scarpetta). You open up about the intellectual & political skirmishes that had taken place during the previous years, when you took uncomfortable positions, one of which was with Lacan, whose Écrits you had read closely & presented on at Yale University in a paper that dealt with "Literature & Psychoanalysis", especially focusing on Lacan's brilliant analysis of The Purloined Letter by Edgar Allen Poe. Even though you didn't explicitly take sides, you did cross political ideologies in terms of the politically entrenched Parisian publications you wrote for or interviewed in. There was something about this matrix of philosophical publications in Paris that was exciting but also poisonous, each one born from an incestuous ideological & political entanglement & rebound from the other. You broke with the review Tel Quel, which meant you broke with its editor & intimate friend Peter Sollers & his wife Julia Kristeva. Asked by some to state your political position you would state back in a letter: "I try never to define my position, in a theoretical or political debate, by giving way to any potential or actual haste or intimidation." It is becoming clear that the friendships that you wore & hung up during this time must have been the filip for your series of seminars in the 1980s on "The Politics of Friendship", which constituted a meditation on enemies as much as friends, the enemy being of the public & of the political, & someone you can love in private outside the public bravado of political performance. Is the enemy just for show? You would substitute old friends for new, such as Jean Ristat & Jean Genet.

Jean Genet, by Brassai, 1948

YOU are only 42, yet homages begin in your 40s. Jean Genet wrote you "a brief letter of homage" in Ristat's issue of the review Les Lettres Francais dedicated to you in '72. It is beautiful! You must have been touched—not a question!

“The first sentence is alone. It is totally alone. But let us read lightly, with a nimbleness that is, if possible, as subtle as Derrida’s, simply, guided by the playfulness of the words, as the full sentence trembles sweetly and bears it on towards the next. The usual, course dynamism that leads a sentence to the next seems in Derrida to have been replaced by a very subtle magnetism, found not in the words, but beneath them, almost under the page.”

SPEAKING of friends & enemies: Foucault? I wonder how you would feel in the context of this biography, when the biographer collages the private & the public through letters & books & anecdotes & whatever correspondence he can get his hands on; how those texts, texts that are less guarded vs those more official documents, throw light on the politics of friendship in the private & public sphere? What happened with the evolution of Foucault's reception to your criticism a decade before, when he thanked you unreservedly for your critical reading of his seminal book History of Madness? Again & again Foucault's private correspondence to you was respectful. Then, a decade later, his public reply--emphasise 'public'—in a series of articles, one embedded in the new edition of History of Madness, explicitly attacks your method, calling it traditional, while also doing a you through his analysis & critique a la Derrida. Your biographer, in one of the rare moments of weighing in on the narrative, suggests your growing fame was a catalyst? For this reader, this polemic comes out of the blue in the biography. The private correspondence between you & Foucault was one that was always respectful & supportive according to the extracts given in the confines & biases of this book. It says a lot of criticism: how it's received, how it can become poisonous over time if not acted upon. Perhaps Foucault had hid his deep-seated feelings from that very first day he read your review leading him to cultivate such a response? If we side with you & say deconstruction is an affirming philosophy, perhaps in its affirmation of the other, its full affirmation of the other's work, it creates a negative in how it shows the other's work back to them, clear as day, without a veil? You, more that anyone know how we don't like to look at our mediated selves. Perhaps close readers are not good readers but 'bad' readers underneath their affirmative gaze?

YOU abstained from replying to Foucault, even when he sent you a copy of the new edition of History of Madness with a dedication apologising for the slow reply to your critique over a decade past. He called your philosophical project “little pedagogy”, which your future detractors would use against you. Your biographer digs up more dirt, an interview with Foucault, wherein he describes “your relation to the history of philosophy as 'pitiful'”. Reading this is quite sad. You must have took it hard. A critique 10 years in the making. If you remove it from its negative context Foucault’s critical description of your method is quite beautiful? Gilles Deleuze, a friend of Foucault, would also say some derisory things about deconstruction with Foucault & Lytotard in attendance around the publication of Deleuze's co-written book (with Felix Guattari) Anti-Oedipus, the first book to fuse Freud & Marx in a philosophical context. All in all there is a sense that you & your method had become too big for such a small circle & the competitive cliques therein. Perhaps that is why, later on, you would return to Lacan through proposed seminars & publications, discovering an affinity in the theory of language & the fame which you both shouldered against the tide of suspicion & envy. After developing a seminar on Lacan with your close & admired friends Jean-Luc Nancy & Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe at the École Normale Supérieure, you helped the two young philosophers to publish a book on Lacan. Posted to Lacan with a dedication by its two authors, Lacan would bring it up positively at one of his packed seminars, not naming the authors, but naming you in your literal absence by naming the unnamed (Nancy & Lacoue-Labarthe) “second fiddles”. Lacan was devilishly brilliant, don't you think? Everything said & done, you seemed to respect his philosophical “cunning” that, in a very real sense, mirrored yours.

YOUR biographer dedicates a chapter to your typographically & formally inventive book Glas. Collonaded with text & margins, Glas is more art than philosophy, or rope-bridges both. After becoming friends through your mutual love of Artaud & Jean Genet, Paule Thevenin, who was the one who tentatively introduced you to Genet, would react negatively & aggressively to Glas, which, according to your biographer, you saw coming. Your biographer is ambivalent regarding the source of this quarrel with Thevenin, saying something in the vein of: ‘she was afraid you would take Genet away from her, like Artaud had been taken from her before’. Strange: this culture of appropriation is to blame once again for the culture of argument. And Genet would receive your gift of Glas “furtively”. Genet had already been appropriated through Sartre's tome Saint Genet, which swallowed Genet whole, turning his early life of thieving & prostitution—in the eyes of Sartre's bourgeois circle—into a moral lesson for the bourgeoisie, & Genet into a saint; once a saint of particular literary gifts into a saint that couldn't write for years after Sartre's 'gift'. You knew what Sartre did to Genet. Equiped with this precedent you rolled the dice once again on a real friendship for the sake of text. You must have really meant it when you said “there is no outside text”! Sartre as your precedent, not to mention yourself as one in your earlier immense reviews in Critique or Tel Quel on the works of Foucault, Sollers, Levinas. You knew how these appropriations weighed upon the writers who received & read them, as if their words were being digested, assimilated, & turned inside-out into a many-eyed doppelganger of the original, all eyes & entries, outward & inward. You were the best reader; Foucault said so. You were the ideal one reader that Nabokov dreamed of. But your close reading was one private thing, your words that followed were another public thing, bigger than the thing that bore them. Private friend; public enemy.

Sergei Pankejeff (The Wolfman)

WITH two young children, something this reader can empathise with, you were neither as free nor emotionally able to leave your children for long periods of time. Travelling to America to teach at John Hopkins University had lost its novelty without a true collaborator; collaboration being something you were becoming interested in your collaborative projects with Jean-Luc Nancy & Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe. Psychoanalysis was playing a big part in your thought process & writing. Your wife Marguerite was studying psychoanalysis. After Lacan read your preface to a book on Freud's Wolfman, he declares in one of his seminars that he himself is the cause of this psychoanalytic turn in you, & he is regretful, intimating you were in analysis, which brought the house down in laughter. You hear about this comedy & the parrying with Lacan continues. There is no doubt that Lacan was your measure in theory & debate, something you needed at this point with all your previous interlocutors disappearing from your gaze? Your biographer, in describing your growing influence in American ivy-league universities such as Yale & what would become “The Yale School”, describes your position in the Parisian scene, after withdrawing from editorial boards of avant-garde reviews Tel Quel & Critique, & drifting from one publishing house to another, as "in the margins". The margins, a la Glas, seemed to be the place in which you always gravitated toward, and your withdrawal from the Parisian centre meant that a polemical stance could be taken. Your growing relationship with Paul de Man grew out of a predilection for the polemical? Whereas your role in education at the École Normale Supérieure, alongside Louis Althusser, was still of central influence in the development & support for philosophy in France. You wrote an admirable article for the newspaper Le Monde, advancing & arguing against the new measures taken by the new government, especially in secondary schools, where the hours teaching philosophy had been reduced massively, writing “the philosophical capacity of a child can be very powerful”.

Emile Cioran, Henri Cartier-Bresson

YOUR very public writing persona is offset by a very private one in the notebooks you began to write in the early '70s. Was Lacan correct? Had psychoanalysis opened the sluice gates for a self-analysis that was dangerous? Your biographer feels uneasy reading these notebooks, even though you chose to archive them for the public to read in the University of Irvine, the home where all your writings were laid to rest. Death had become a preoccupation, thantos your passenger entwined with the eros you felt for your boys, your children, whose very existence & protection became almost unbearable as they became more independent & went out into the world alone without you holding their hand. In your sons' correspondence with your biographer they speak of your great anxiety back then. Through them you revisited the racism you experienced as a child; you dug up the death of your father, something this reader had forgotten to recount here after it was mentioned earlier in the biography. Your notebook writings are more in the vein of Nietzsche or Emile Cioran. Did you read Cioran? Beautiful. Sometimes writers feel they have to go deep into territory that is dangerous to find a style that surprises them. Was this the reason for bringing this anxiety upon yourself in order to discover a new style? A soul-beating of sorts? This reader thinks that the personal affairs of your life, outside & inside the text, inside & outside the home, all went towards the same project of deconstruction. Your life, your autobiography, which was becoming visible in the texts like never before, was affording you a way of realising a new way of writing. The circumstances of your life, love or other, were elements that were hard to separate from the progression you were making in your writing. Everything was lending itself to your ambition to write from the basement in the attic that had become your new cubbyhole with a “trapdoor” & a scarf to fend off the cold.

Friedrich Nietzsche

SPEAKING of your biographer & speculation, in this part of the book & period of your personal & working life, there is, what reads like, a lack, or nostalgia for the 150 pages previous—two decades in years—regarding other voices, with the cri de cœur of Michel Foucault or Philippe Sollers absent, voices that spoke with & against your texts with such eloquence & heat. This lack is gradually being substituted with your personal correspondence with yourself or others, which has turned the perspective of your thought inward, lacking the political & critical frisson of your past interlocutors, who have gone silent. The eloquence of your writing, breathtakingly lyrical & confessional at times, has replaced, for the time being, a lively public sphere where criticality, instead of a dreamy navel-gazing (& you know how Freud & Lacan described the inpentratable navel of the dream), can revolutionise discourse, your own & others. As Nietzsche declared: “And so let us bear with each other, since we do in fact bear with ourselves; and perhaps each man will some day know the more joyful hour in which he says: ‘Friends, there are no friends!’ the dying wise man shouted. ‘Enemies, there is no enemy!’ shout I, the living fool.’”

THE PUBLIC (via the media) came clamouring soon after your intense first-person phenomenological search into being with the explosion of the “New Philosophers”—which always looks & reads & sounds better in French: Nouveaux Philosophes. Led by Bernard-Henri Lévy (due to his mediated good looks, vanity & ego) the Nouveaux Philosophes defended & utilised the media to disseminate philosophy. A post-Marxist or neo-Marxist philosophy that, in Gilles Deleuze's words “is crap”. Deleuze's irritation had something to do with the dumbing down of philosophy & a binary argumentation of philosophical principles. You were always more cautious with regards to Nouveaux Philosophes (maybe less so with Bernard-Henri Lévy), especially in what you believed was a powerful medium to relay a message. It's fascinating that you wouldn't give photographers permission to take or use your image until the Nouveaux Philosophes turned up? Unlike Deleuze, you felt that such a mediated entity like the Nouveaux Philosophes would “grow… every time anything advances onto their ground”; & that silence (a Derridian defence) “can sometimes be more effective, more intimidating”.

Bernard-Henri Lévy & Derrida wrangle in the Sorbonne, 1979

DID you personally dislike Bernard-Henri Lévy, who was, as was proper & appropriate in this new mediated age, abbreviated to “BHL”? This reader read a recent article on BHL titled, something like, ‘Why is it so easy to hate Bernard-Henri Levy?’ You also might like to know that BHL wrote a biography on Sartre which is more BHL than Sartre. Deleuze's rant on the Nouveaux Philosophes mentions a “return to the author”, “self-importance” & “vanity” as determining factors of their project. BHL admits that he came for a fight the day of that infamous meeting in the Sorbonne, with over one thousand two hundred in attendance, to appeal the new changes to philosophy that were being proposed by the state. BHL said he was “beaten up” in his effort to grab a “microphone”. The biographer gives a taste of what was said in the transcript & its it's less dramatic than BHL's account. Perhaps he was performing for the camera? You had time for the Nouveaux Philosophes but perhaps not for BHL, its ringleader? Your biographer, albeit in a footnote, notes how insightful BHL could be. He was cynical, yes, in terms of your philosophical project being ubiquitous & outmoded, but his discussion on Marx & you, Marxism being something you believed BHL wasn't deserving of being aligned with, is interesting, in how he observes that you outflanked Marx, some twenty years before you wrote Spectres of Marx. What is most interesting in this debate with the Nouveaux Philosophes is your use of the word “affirmation”. Not in how we use the word today in an emotionally supportive way, but as declaring that you understand, you hear, you nod in affirmation of the existence & purpose of the other, without having to agree with the other. To affirm, in your vocabulary, is to notice the other, & reply in kind, without seceding, in this case, to the Nouveaux Philosophes. As you said in a recorded interview three years before your death: deconstruction is “an ethics of affirmation... attentive to the other”.

AVITAL RONELL (today a prominent New York intellectual) introduced herself to you in 1979 as “Metaphysics”, & who, to your dismay, ended up dating & living with your son Pierre, 11 years her junior, aged 16. The account your biographer gives of your first meeting with Avital Ronell is fascinating, & the knot that formed between your personal & professional life thereafter. These flirtations, both in professional & familial relationships, dotted throughout your biography, suggest, in the lifeworld rather than the letter, a distance, a separation from those you loved in your writing. The page, the piece of rough paper & ink that you loved to pour & thread the signature of your relationships with those you loved in the lifeworld, is evidence that you loved greatly & carefully (equivalent to your word choice). Your sons say you were not close; Avital Ronell describes that your effort to shield & protect your children from the lifeworld was absolute. Is this love? A protective father? Some say that the life of a writer, who is also a reader, is one of fear for the lifeworld, & perhaps in your case, with your 60-odd books, a fear for the lives of those close to you in the lifeworld? This—what you described in an earlier letter—“split”, also seemed to divide your writing & your living, if one were to call writing a form of withdrawal from living. If deconstruction - deconstruction not being a deconstruction of one thing but of two relationships, such as the hierarchy & privileging of speech over writing, or presence over absence—then your immediate & personal deconstruction was the centre where the play of life & writing jostled in a democracy to come. Your dualisms were self-perpetuating, in writing, in love, in life.

Louis Althusser & Helene Rytmann

IN the early '80s, just around the time your wrote The Postcard—an ode to the love letter, love letters to whom you do not disclose—Louis Althusser strangled his wife during a psychotic break, while Lacan, Barthes & Sartre where laid to rest in the space of a year. Two generations of French philosophy gone. Everything was changing. Publication houses were becoming more resistant to difficult philosophical texts. Your friend & teacher Paul Ricoeur turned up to teach one day in the university where he headed the philosophy department & was greeted by one student. Before he quit, Ricoeur asked you to take his place, which you did, reluctantly at first. Retrospectively, your reluctance was merited, as the to & fro for positioning post-Ricoeur was bitterly contested. The resentment to your philosophy & fame came out of the shadow of the educational institutions into the light of day in the silhouettes of past students & university committees who, when you went for the interview for the vacated Ricoeur post, taunted you by reading extracts from your books, especially the most recent, in which psychoanalysis & literature were vying with philosophy. Your early philosophy had tinkered with the very foundations of Western philosophy & your peers' treatment of that tradition. Now (to their minds) you weren’t even a philosopher.

Jean Paul Sartre's funeral, 1980

THE day of Jean Paul Sartre's funeral, 50, 000 people thronged the streets of Paris. Concurrently, your generation, including yourself & Foucault, were being attacked in print by the Nouveaux Philosophes generation. When Althusser avoided trial for the murder of his wife--instead interned in a mental institution—this was another nail in the many coffins that were mounting up at the Ecole Normale Superieure with regards to the old philosophical regime being replaced by the new. Your biographer recounts how you were there for Althusser, visiting him throughout his internment & the following condemnation of his theory (as an eminent Communist Party member), even though you were split in terms of your theoretical or political leanings. These splits preceded you in America too, where your supporters at Yale, Paul de Man & J. Hillis Miller found themselves defending you against your American detractors, who believed, it seems, that Paris was right in their resentment, or in Nietzsche's terminology ressentiment, wherein the feelings towards the other become more & more poisonous as resentment is turned inwards. Your arrest in Prague after drugs were planted on you by a young & ambitious new head of police to intimidate the Hus Foundation that smuggled 'education' into Czechoslovakia by way of seminars & books, put you on French TV like your media-savvy rivals the Nouveaux Philosophes. Your image & words broadcast to the French nation caught the attention of friends that had ceased correspondence with you, like Peter Sollers & Michel Foucault, the latter you would mend relations with before Foucault's death in '84, aged just 57.

Derrida & Pascale Ogier, film still, Ghost Dance, 1983

YOUR son Pierre passed the École Normale Supérieure agrégation (exam) on his first try; it took you two tries. He chose philosophy; one teacher responded that by retaining the name “Derrida” Pierre was “committing suicide". You made an appearance in the film Ghost Dance. After the experience you would make the most remarkable observation, considering where we stand now in relation to technology: “I think the future belongs to ghosts, that technology increases greatly the power of ghosts.” Ghosts from your past were rising in every part of your life, from ex-friends & students that stood in your way of acquiring teaching posts, which you desperately sought, to your own ghost in terms of not being named in a “wide-scale” survey of the 36 most influential French intellectuals. Remember Bernard-Henri Lévy (BHL), he placed 9th! How did you feel? Your biographer speculates “hurt”? Your discretion in terms of a mediated persona/ image didn't help you. Even though the image was catching up & passing you out, something you would succumb to soon enough. Your friend Paul de Man would succumb to cancer. The tally between friends vs enemies was going the wrong way. You would try to recruit acolytes for teaching positions in a new university. Philosophy was on the agenda of Francois Metterand, the new French president, after being nearly razed to the ground by his predecessor. As director, you were one of the very few to nominate female candidates for the roles, one being Avital Ronell. She said: “He'd told me, in the first days of our relationship, that one day I would make war on him, whereas I'd decided that this would never be the case, at least not on my initiative.”

Marguerite & Derrida, 2000s

YOUR biographer has split your life into three parts; ‘Part III' begins with the death of Paul de Man. Your wife Marguerite is but a ghost up to this juncture of the book (350 pages in equating 50 years of your life). She stayed with you till the very end, appearing in the late documentary about you, sitting by your side, still calling you “Jackie”. Marguerite would live for 16 years after you pass; she died of Coronavirus in March of this year. As someone who was practicing psychoanalysis, defined lazily as ‘the talking cure’, she would place more value on the ear, mirroring Adam Phillips' definition of psychoanalysis as “the listening cure”, but in her case the listening seduction: “I've always thought that it was mainly through his capacity for listening that Jacques could seduce women.” You would emerge from this period of gossip & secrets through written words that confront mourning & memory. However the intellectual landscape post-Paul de Man was one of hostile winds from the West & circling winds at home. Yale academic Ruth Barcan Marcus would go as far as sending a letter to a French minister to remove you from Yale because of your “terrorist obscurantism”. Cross an academic eh! Whereas at home the publication of French Philosophy of the Sixties was not as banal as the title suggests. On the contrary, your biographer describes it as an “‘uncompromising dismantling of French Marxism, of French Heideggerism [YOU] and of Freudianism a la francais’, before calling for 'the renewal of an authentic critical philosophy’.” The lot of you were lined up against the wall; you were given a whole chapter for your “dismantling”. Interesting that your biographer uses the word “dismantling”, one signifier of 'deconstruction' in the French dictionary, which is exactly not what the authors (Luc Ferry & Alain Renaut) of this polemic were doing to you & your '60s peers. They had no intention of putting you all back together again.

Derrida, Algiers, 1984

THE mid 1980s was a time of fending off attacks on all sides (or staying silent), whilst forming & fusing other institutional alliances (which always seemed temporary—by accident or intention) to sustain a philosophical project that was under siege by both French & American audiences who, it seems had stopped reading you, which allowed them more time to mount their attacks, which were perennial & vicious. One attack after another, how did you keep moving forward under the rain of ink? Your prolific writing & reading (even a sustained effort to master Shakespeare) suggests you were turned on by this giant offensive. You would also turn your eye back to Africa, the North of which you & your family were exiled from, in the figure of Nelson Mandela, contributing to the book For Nelson Mandela, alongside Susan Sontag among others. (btw: Susan Sontag died the same year as you - 2004—three years your junior, aged 71.) One of your thesis students back in France, even after advice had been given to not read you, & would probably mean she was finished in the university, said that's what she liked about you, the threat to the institution you posed out of your flagrant show of independence. You would leave Yale for Irvine University California with J. Hillis Miller. There you would deliver your French papers in English, first very awkwardly, but then more refined, discerning “the shades of meaning between maybe and perhaps”.

Derrida & Pierre Bourdieu

1987, Victor Farias' Heidegger and Nazism resurrected the question, the hesitation, the conflict in reading Heidegger, for the media at least. Heidegger's Nazism was a debate that had played out for years in academia: so, in secret. As early as '69, your articles, influenced by Heidegger as they obviously were, were cast under the shadow of fascism with the publication of this book & the following newspaper articles. Your philosophical project was also brought into question. The French media saw a headline, proliferating a wave of headlines, such as "Heil Heidegger". You being both the most famous & unknown philosopher of Heideggerian bent in town, got the brunt of the aggression. It was Heidegger's silence & your silence that was the sore point & point of attack. Article upon article piled on your resolve, which resulted in a series of retorts you wrote & conferences you took part in, where the facts of Heidegger's Nazi party membership vis-a-vis his philosophical corpus were discussed. Sadly, Pierre Bourdieu, a classmate & contemporary of yours used Heidegger to dethrone philosophy & you with it, in a newspaper article, wherein he called out French Heideggerians to answer the moral & ethical implications of this closeted nazism.

Paul de Man

MORE of the same would be visited upon you when your late friend & interlocutor Paul de Man's past, like that of Heidegger's, was found to have fascist origins, as articles he wrote for a Belgian newspaper as a young man revealed an antisemitism that could not be denied. You were one of the first, as a friend & colleague, to propose that all the articles should be made public. You also declared the “wound” that opened up for you on reading them. That didn't stop you defending him in print. Out of loyalty or friendship, even your closest peers felt that your deconstructive responses in print to this blatant antisemitism, especially being one who experienced it as a young Jewish boy in Algiers, only fueled the resentment that you & your deconstruction & your followers had brought to bear on philosophy. Marxist critic Terry Eagleton calls your biography “brilliant”, but your writing concerning the De Man affair, “disingenuous”. Indeed, silence could have been your friend at this time, but as you write in a remarkable extract, fortunately shared by your biographer, a paragraph that this reader will read again & again at times of critical hesitation, & repeat here in full.

“When I try to think, work or write and when I think that something ‘true’ needs to be put forward in the public space, on the public stage, well, no force in the world can stop me. It’s not a matter of courage, but when I think that something needs to be said or thought, even in the ‘true’ but as yet unacceptable way, no power in the world can discourage me from saying it [...] I have sometimes written texts that I knew would cause offense. They were, for example, critical of Levi-Strauss or Lacan - I knew the milieu well enough, after all, to know that this would cause a stir - well, it was impossible for me to keep it to myself. This is a law, it’s like an instinct [or drive (pulsion)] and a law: I cannot not say it. Between you and me, sometimes when I was writing this sort of text, a bit provocative and polemical in some circles, writing something and then, as I was just drifting off to sleep, half-asleep, there was someone inside me, more lucid or vigilant than the other, who kept saying: ‘But you’re completely crazy, you shouldn’t be doing this, you shouldn’t be writing this. You know perfectly well what’s going to happen…’And then, when I open my eyes and settle down to work, I do it, I disobey that council of prudence. That’s what I call the instinct of truth [pulsion de verite]: it must be said [avoue].”

AS mentioned, your biographer has split your life into three parts, but those parts are split further into chapters, covering one or two years. They are packed years; packed by events that accumulate in terms of books & events to come, & the memories of those books & events past. It's a turnstile: people & books going back & forth in rush hour, their direction dependent on how alliances are forming or breaking that year, as you fall in & out of peer friendships that were very much part of your life, to drift away, disappear, or reemerge, either as detractors or Derridians. Is there a grey area between those poles, those hierarchies, as there was in deconstruction? It takes two to argue. You invited this onto yourself from the beginning. Levi-Strauss, Foucault, Sollers, Kristeva, you read them all, you read them well, you read them best, you read them so well that you found them, inside-out, & you showed their insides back to them. Narcissists don't do well with mirrors. You know that as much as anyone. Your way with friendships is complicated & enigmatic. Between '88 & '90: Lacan would be remembered by you as a friend & enemy respectfully in a dedicated conference; Alain Badiou would fall out with you because your presence was saturating the same Lacan event; Julia Kristeva would cynically attack you in a roman a clef; you would break the theory triad between you, Phillipe Lacoue-Labarthe & Jean-Luc Nancy as the unsaid tensions following the revelations of Heidegger's nazism (& Paul de Man's) took their toll on Lacoue-Labarthe, compounded by his alcoholism; Jean-Luc Nancy would go for a heart transplant, bringing you both closer, & Nancy, you might like to know, would survive & live to this day (aged 80); your son would graduate from the École Normale Supérieure, change his surname from Derrida to Alfiera, publish a book, take & leave a teaching job, & become more like you in resisting being like you; Louis Althusser would die, & you would meditate on your mother's old age, Alzheimer's, & ultimate death alongside a young Geoffrey Bennington in Circumfession—btw... Geoffrey Bennington translated a new edition of Glas. The cover is enigmatic.

THIS reader is a ritual runner, like you were for a stint in California in the '80s, running to organise your thoughts, taking notes as you did, text following you everywhere. Your biographer, in a chapter entitled 'The Philosopher at Sixty', hopscotches through the idiosyncrasies of your personality in a thematic rather than the chronological order that has defined this biography & led to this idiosyncratic chapter. The chapter begins with an unpublished questionnaire that you felt “too revealing”, & your biographer, up to now has only flirted with your lifeworld, the world both outside & coyly inside your text, suggesting there is an outside to your text in his portrait. So this is the biographer's baggage, the lifestyle section, the gloss of the magazine that you kept private, secret, as its shine & shallowness might bring something to your text that would only distract or corrupt the reader & reading. As you say & imply repetitively in your documentary: the philosopher's politeness with regards autobiography is the biographer's indecency. This is very much the matrix of clinical psychoanalysis: the analysand's shared & known autobiography vs the analyst's unknown or fantastic biography. This chapter feels like a guilty secret, like the guilt you felt watching soap operas. It is not you confessing, but your biographer's confessions. Your obsessions are the same realities & fantasies as everyone else's. Your archive fever & superstitions are variations of the other's. Your regrets, cliche. This is an epilogue or afterword before the end. It is an appendage where extra was not needed. What this chapter does do is reinforce that something does indeed wander, from time to time, outside the text, like your biographer has done here, & that wandering is not necessary but perhaps-maybe needed. The running helped to clarify this aporia. Thank you!

Ed Ruscha (detail of) The Los Angeles County Museum on Fire, 1965–68, oil on canvas

AVITAL RONELL describes the essence of you at this time as "quietude". The foundations of philosophy & its traditions were floating beneath your calm & attentive-to-the-other attitude. This reader now remembers something you wrote in a letter to your great friend Gabriel Bounoure in 1967: “I am walking on ground that is forever giving way.” That was quarter of a century ago, a time when your philosophical project was just beginning, & when you seemed scared of what was happening beneath your feet as if, to go further, would lead to nothing left to support your falling body. But you had no need to worry; no foundations & there you are, sidestepping on the pebble remains of the institutions that bore the weight of the nimbleness of your freeplay. “I believe that one does not wage war on institutions except in their name, as if to pay them homage and in betraying, in every sense of the term [i.e. also making manifest] the love one bears them. [...] …there is no absolute exteriority”. Sartre said somewhere that "the rebel" wants to keep society the way it is so as to have something to rebel against, whereas the revolutionary wants to upturn society in order to have something brand new & start again. What were you? The institutions that rejected & reluctantly accepted you in the '90s seemed to paint you as the rebel but fear you as a revolutionary. You wanted to be accepted into the College of France where - what Pierre Bourdieu described—the “consecrated heretics” taught, like Foucault or Bourdieu himself, who tried but failed to get you voted in. Then there was the honorary degree from Cambridge which created an outcry from a murder of philosophers that declared in a letter to The Times London that your were a “nihilist”, & better still, a "Dadaist". What flattery! Of course you didn't take it that way. But history was made when a vote took place over what was now a media issue that would have made Bernard-Henri Lévy of the Nouveaux Philosophes proud. You won the vote: 336 to 204. Not a landslide, but there's flattery in those 204!

Fall of the Berlin Wall, 1989

THE details of your biography are becoming less important for this reader as the great heft of this hardback is behind. A pencil, a bookmark, creates a wave of white from binding to edge—time, tiredness, elation, all in that ghostly white block of a life lived. Your book Spectres of Marx, your first public confrontation with Marx, & timely one, just four years after the Berlin wall fell, was a long time coming. You waited until the Communist regimes feel, the dust of an ideology pumping its fist in the air, before you wrote. You said years before, when friends & peers wondered & wrestled with your political position, you needed to “do the work” on Marx. Never a Marxist or a Communist, this ghostly tome, written over five weeks in an explosive production, as it lay latent in your white bones for decades, was celebrated by those peers & friends who did take a side, & because it was you who wrote it, the reluctant side-taker, it was all the sweeter. It made your wife Marguerite weep, as if she knew something about the depths of you that others never would, this biography would never touch. Spectres of Marx was a political act that, although ghostly in name, reified your political intent & interventions in political matters. You would show your colour for the first time. And, as always, Spectres of Marx came from a place of asymmetry. The euphoria that you witnessed in the efflorescence of liberal democracy, another ideology, was something you did not witness in the real world, on the ground, where the same social subjugations were pronounced in the dirt of society. Two awkward friends & peers would die by suicide, Sara Kofman & Gilles Deleuze, & another less awkward friendship by old age, Emmanuel Levinas. You would write & speak on the occasions of their deaths, like you wrote on Marxism after it was buried. But your homages would never be sentimental, they would always be awkward in sentiment, revealing the Politics of Friendship, for this reader, one of your most revealing texts, on which your biographer exorcises you in one sentence: “Friendship was [your] first criterion of choice.”

Derrida in Dublin with James Joyce

FIFTY pages to go & the feeling is the biographer is winding things down as your eminent death is pages away. The infusion of detail & concentration & community that invigorated the biography of the '60s--a time in which this reader would have loved to participate—has become scattershot as your travels take you everywhere, even Dublin, to stand beside James Joyce on Talbot Street in the rain. Dates are less significant as the biographer tracks back to try to connect things, not in an anachronistic or revisionist way, but to bring some 'body' to your fragmentary & torn activity in these later years, when your mediated image became more commonplace & famous in the American & even French media through the form of the interview. The ethical & political turn in your philosophy also became more explicit, with a message that was less indebted to the canon of philosophy or literature, & more indebted to the histories of subjugation & power in the name of Communism or Democracy. Your body, under the strain of your reputational economy, was being spreadeagled by what one French commentator coined “Derrida International”. You were everywhere & nowhere; a known quantity & enigmatic quality; a bodily presence & theoretical absence. Some 67 books over 34 years, you had exhausted language to the point that you were making up new words, most famously & officially “différance” with an ‘a’. (Ha! Google still automatically responds to this search with dripping irony—"Did you mean difference?") You, at last, give way to the mediated image of yourself, inviting cameras into your life to lay vigil on your every move, a surveillance that up to now you warded away like a superstition, superstitions finding a haunted home in your obsessive temperament.

Derrida & Jean-Luc Nancy

MEMORY, or a greater trust in memory, is playing a bigger role in the recollection of reading these last pages. You wrote a book for Jean-Luc Nancy, “On Touch”, once again finding something in the margins of Nancy's philosophy that he himself could not appreciate, which he learnt & admired through your close reading. Nancy thought it was “too much”, two words that have been used repeatedly to describe you: “too much”. This “too much” could be used for David Foster Wallace, that writer of maximal descriptions & verbal vision that became tunnel in the eye of “too much” world. The emergence of the private sphere in this new mediated world of publicity & promotion, wherein the private (the secret you) is not maintained, means, in your words, “we are in a totalitarian space”. Disclosed secrets in terms of your political alliances would emerge in your writings on Israel/Palestine & 9/11. Alain Badiou would describe the political qualities of your thought as “courageous... because you always need great courage not to get caught in the division that has been set up”. A division with Jürgen Habermas in terms of philosophy (spanning 12 years during which time bitter things were written & said) was mended in the name of politics, a strange irony, especially when you read your papers on the “Politics of Friendship”, where you describe politics as a sphere that is dependent & sustained by the public enemy. This rapprochement with Habermas would coincide with Germany heralding your name via the Adorno Award, the most significant prize of your career.

Derrida’s library

READING a life is not living that life. Throughout this reading of a life, yours & not yours, the abundance of letters that you wrote, especially in the middle years of your life, has made this more of an autobiography at times. Towards the end, your letter writing lapsed, your correspondence evaporating in the ear of the other. If we take you at your word, that the philosopher's text is more biography than the biographer's text, then all the papers you delivered throughout the world in the last five years of a life gave those that were present, if they read & listened the way in which you prompted in your writing, a life in words. Your archive fever during this period reaches the tips of your fingers, as those around you interested in legacy, proffer the question “after life?” You are vibrating with questions that precede death: religion, death penalty, cremation, the latter two never treated in philosophy. Under the weight of this imminence, your reading of psychoanalysis, a passenger to your thinking since the '70s, is a supplement to philosophy's misgivings over the psyche. You are diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, the same thing your father died from. You undergo chemo. Your friends find out; the heart pouring begins. Biographies are one life, not many, even though the other was something that you forcefully reached out for in your philosophy. Lives have come & gone in this biography, a line or two to mention the other's passing. Your last years in words feel long; this reader wants violent lighting to blossom in the night's sky. There's nothing romantic about the waiting room of terminal disease. Marguerite weeps, friends weep, peers weep in words. Why is this? Why do we cry for the other? Is it the grappling with absence, an absence that you wanted the reader to see as a presence in your philosophy? Why “after life” do words from the other come flooding for your attention when you cannot attend to them? It's perverse. Although fatigued & unable to write you continue to attend conferences. Beautiful things are said & critical things unsaid in your presence which you must have taken to heart but questioned the timing & occasion.

Derrida waving to the other (with Avital Ronell) 2003

IN the summer of 2003, in Jerusalem, you gave a lecture on Paul Celan, after which Dominique de Villepin gave a tribute, the best this reader has read, as it turned what was deemed the nihilistic tendencies of deconstruction towards the light of affirmation:

“Jacques Derrida, you give density back to the strongest and most simple words of Humanity [...] ‘Deconstruction’ is an attentive, scrupulous, activity, a thinking which takes shape as it rests out its object. An extremely creative, and liberating, activity. Undoing something, without destroying it, so as to go further.”