MADDER LAKE ED. #17 : TOWARDS ✖️ EVA

EDITIONS

EVA '14 artist David Horvitz caught on camera just before our on-the-hoof conversation in Dublin's Phoenix Park, 2014.

In 2014 I was selected for EVA International by curator Bassam El Baroni. My formulated role within the Irish Biennial was Fugitive Art Critic, wherein I possessed the same exclusive access and privileges as the other EVA '14 artists. Equipped with this agency my objective was to get up close and personal with the EVA artists and curator so I could write in a deeper way to the sweeping arc of an art press subject to editors, word count, deadlines and so on. It was both an exhilarating and exhausting process that included writing, interviewing and presenting in public. So exhausting in fact that two years later I still couldn't bear attend EVA International 2016.

Last year I applied to EVA once again with a proposal. It was rejected. But I started to question (only this week) whether I could still make the work, or at least a version of the work. I began to wonder what becomes of the proposals that were not selected for EVA ’18 or similar open submission opportunities. Are artists just motivated by the ‘stage’ of EVA? Do proposals die a death after rejection or can they be resurrected on another stage? Or have artists become so dependent on the teat of wet-nurse curators and art institutions that PFOs are a death sentence?

So I have decided to do something with my rejected proposal that will involve EVA ’18 (unofficially). For now I have pasted below my first 'address' to the artist Patrick Jolley written in 2014, which was posted on billionjournal.com during the first week of EVA ’14.

18.4.2014.

#1/ ‘Dear Patrick Jolley’

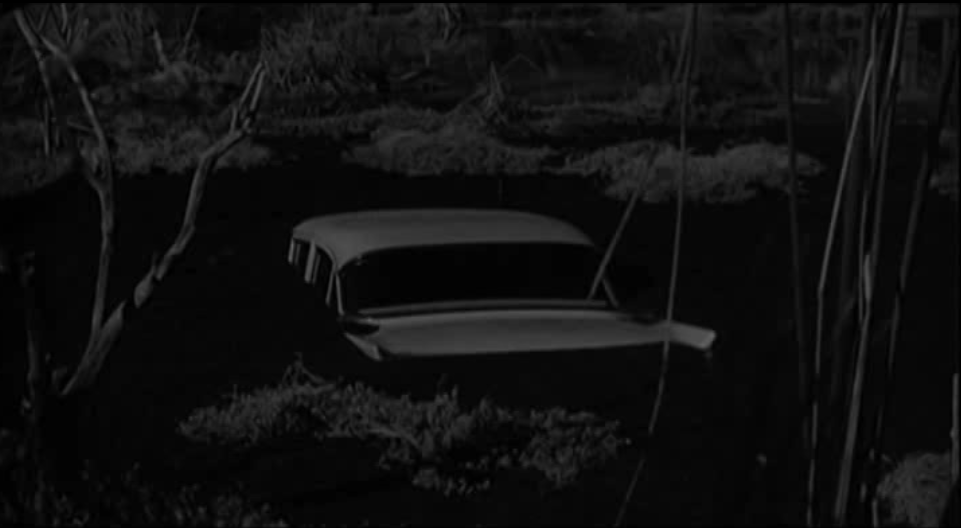

PATRICK JOLLEY, This Monkey, 2009, Haryana, India (7m), 16mm, b/w col (film), EVA International 2014, Kerry Group – former Golden Vale Milk Plant, Limerick City; photo: author.

“If animal life and human life could be superimposed perfectly, then neither man nor animal – and, perhaps, not even the divine – would any longer be thinkable.”

“man is a fatal disease of the animal”

‘Dear Patrick Jolley’ is the first of a series of textual responses which take the form of a review/letter addressed to selected EVA artists. It is left open to each addressee artist to respond in his or her way, or not at all. This textual component compliments and completes the ongoing ‘recorded conversations’ portion of +billion-’s discursive project for EVA International 2014.

***

Filming in Delhi in 2012, Patrick Jolley suddenly died at the age of 47, just when his art was taking flight. Considering my discursive project for EVA is built around conversations with the curator and selected artists, Jolley’s art will have to speak for itself. The following is a response to This Monkey (2009) installed in one of multiple warehouse spaces at the Kerry Group Plant venue for EVA International 2014.

***

I never knew or met Patrick Jolley. To my knowledge, I never saw him from a distance. He was never pointed out in an art context that may or may not have interested or suited him to attend. He was never mentioned in lectures or by tutors or other students in art college. Strangely, there’s nothing much written on his work. A scattering of unfocused articles. A few blogs mention his films in a fanboy way. The ‘reviews and essays’ links on his website are ghosts. I know nothing of his emotional or physical makeup as an artist, acquaintance, friend. His gait? His ideology? His smile? His awkwardness on first meeting? His fears? Google offers a couple of head and shoulders portraits. Another shows him standing with his early career collaborator, Reynold Reynolds. Although his online persona is shy, there’s enough physiognomical information to tell me that he is the star of his own short film, Snakes (2009), one of my personal favourites, and an unofficial partner to his submitted film for EVA International 2014.

Why a favourite? Well, it’s like the crescendo of anxiety performed in his other film works has transitioned into a diminuendo of acceptance, as he lies on a bed, unflinching, while snakes rummage in his cheap suit and coil around his flaccid body: the tension that exists whilst watching is ours, not his. Snakes tells me that fear was something that Jolley exposed himself and the viewer to, time and again. Burning, drowning, falling are oneiric contemplations that temporally unwind the spool of his art. However, sometimes an air of despondency overwhelms the traces of humour. All stick and no slap. No tickle. Other times I am reminded of Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead, with the extreme stop-motion expressions and animated hi-jinks. Other times, again, I feel I am being dragged by the vestigial tail through the dregs of humanity’s apathetic self- and other-destruction. I make a point about humour because it’s as if humour is the one thing that fails to push through the grey unheimlic of his cinematic architectures. He threads those lines that separate laughter and fear, madness and sanity, human and animal, life and death. All of which seem to sidewind purposefully throughout the body of his film work.

Of course, emotional subjectivities are attached to watching his art and its future promise unfulfilled, casting an emotive spell that perplexes judgement. His seven-minute short, This Monkey, is one such emotive animal, that compounds those inherited and unavoidable subjectivities. On the opening night of EVA International 2014 the rumours were flying and mythologies were already being formed around the artist’s rarely seen short. Submitted by his estate, curator Bassam El Baroni admitted that, not only was he “blown away” on first viewing the film, but This Monkey suggested different curatorial avenues, other artworks, alternative ways of thinking about the exhibition. Those that visit EVA would not be blamed for thinking that Noah has come ashore in Limerick City.

Whilst first experiencing This Monkey on the day before the official opening technicians were swarming the Kerry Group Plant and midges bunched in the red sun. No artwork labels, I was physically and emotionally sold before the credits told me Patrick Jolley was its author. Projected square, large and raised, alongside Hassan Khan’s complimentary but more irreverent The Dead Dog Speaks (2010), Jolley’s This Monkey seems to breathe textures; environmental textures that swap back and forth between belonging to the industrial tomb of the warehouse, with a great facility for holding the cold, to the implied heat of the rural and urban settings of Haryana, Northern India, where he shot the film in 2009. A sound dome localises the haunting composition by Brian Crosby in place, but not to the point that the overall ambience of the warehouse is not affected by the charango acoustics and charged foley.

What resonates long after experiencing Jolley’s This Monkey, in what seventeenth century English philosopher John Locke described as the camera obscura of the brain, is the enigmatic images that veer away from the norm. “The understanding is not much unlike a small room [un cabinet entierement obscur in Leibniz’s French] wholly shut from light, with only some little openings left, to let in external and visible images; would the images coming into such a dark room but stay there, and lie so orderly as to be found upon occasion, it would very much resemble the understanding of a man.” Jolley’s This Monkey is one such cabinet entierement obscur, albeit a disordered and discordant one. Surprisingly miniature and windowless playhouse corridors weave past the artist’s fidgeting lens. Corridors wherein rhesus monkeys flirt wearily with the camera as if in a cognitive experiment conducted by a dicky-bow wearing David Lynch or Jacques Lacan. Anthony Vidler (The Architectural Uncanny) writes via Leibniz and Deleuze: “So the closed room, itself a soul, has no windows. Its only furnishing, to use Bernard Cache’s term, is that of the screen, which represents the brain, a pulsating, organic substance, ‘active and elastic,’ ‘not unified, but diversified by folds’.”

Jolley makes us squint anew when rhesus monkeys are seen feasting on what look like beef jerky remains of humans with extra barbecue sauce. Facetiousness aside, these moments are anything but ironic. Given that we share over 90% of our DNA with the rhesus monkey – making them the preferred ‘soulless’ receptacles for experimental psychology during the twentieth century – Jolley’s involved vignettes rewind the brutal ‘pit of despair’ attachment and deprivation tests on our primate cousins, carried out in the ’70s by American psychologist, Harry Harlow.

If you are not from the Indiana Jones generation, in which the rhesus monkey is the clever minion of the patch-eyed no-gooder, This Monkey portends to a steam of consciousness being emptied out before humanity wakes to a New World. A post-human world removed of human tinkering. In fact, humanity as we understand it – ethically and lawfully – evanesced. The science-fiction trope of post-apocalyptical existence, in which humanity is searching through the ruin of its own nuclear, ecological or technological mistakes, is replaced in Jolley’s This Monkey by a world perhaps absent from hubris, progress, history, philosophy. A Garden of Eden minus the apple monger. French philosopher Alexandre Kojève – to whom I will leave the last words before they vanish beyond readability and relevance in the wake of Jolley’s simian send off – writes that Post-historical man will be ‘reanimalized’ in his absence:

“The disappearance of Man at the end of History is not a cosmic catastrophe: the natural World remains what it has been from all eternity. And it is not a biological catastrophe either: Man remains alive as animal in harmony with Nature or given Being. [...] Practically, this means: the disappearance of wars and bloody revolutions. And the disappearance of Philosophy; for since Man no longer changes himself essentially, there is no longer any reason to change the (true) principles which are at the basis of his knowledge of the World and of himself. But all the rest can be preserved indefinitely; art, love, play, etc., etc.; in short, everything that makes Man happy.”

![MADDER LAKE ED. #10: TOWARDS A HABIT [ psychoanalytically speaking ]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/594626eae3df28301b1981dc/1513427037670-14LCX8VBQFY0V1FCMR03/gober-circa-1985.jpg)