PAUL DORAN

PAUL DORAN:

THE DEEP—SEATED INTERVIEWS

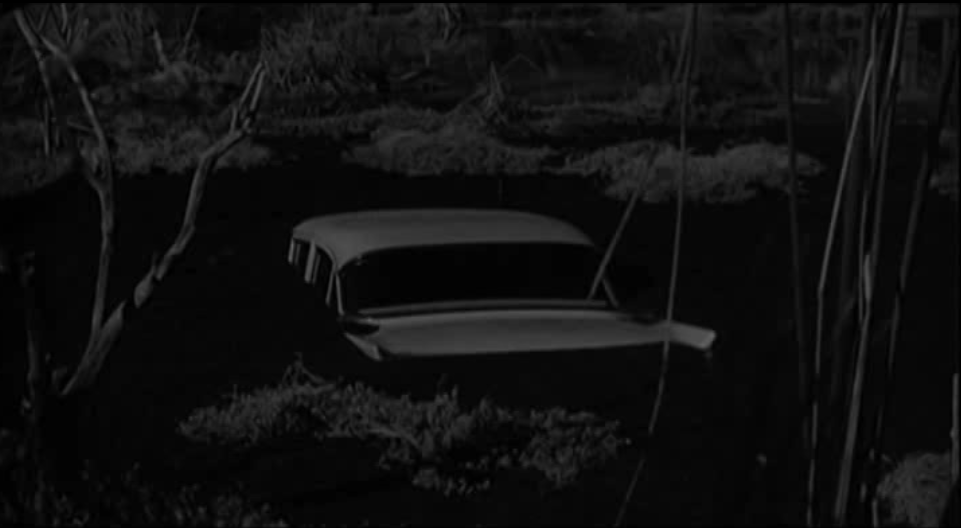

Paul Doran, Sky Shelter (2013) wood, acrylic paint, 16.5 x 45.8 x 18.9cm

James Merrigan: I thought we could start with education. I am curious about the different paces of education when it comes to learning or evolving a painting identity. In art school a painting identity can be fast-tracked over the course of a four year degree, whereas a painting identity might never be pinned down without attending art school. Following art school things slow down, speed up, or continue on as they were, when the painter returns home to a self-driven and self-directed education. Chris Martin said somewhere in an interview that it took him five years to get rid of what he learnt in art school – I think he used the word “vomit”. You developed a very distinctive painting identity during art school. Between art school and home your painting identity has emerged over 20 years. I use the word “home” intentionally because the last time I visited your studio, some six years ago, it was in your home. Can you discuss the nature and nurture of your painting identity between art school and home, and what has fed and continues to feed into your ever-evolving painting identity, in terms of teachers, lecturers, peers, friends, history and time?

Paul Doran: I have mixed views on education; the one I received and the one that I try to give as a teacher. I left school in 1990 and went to IT Waterford to study art. I left after one term, totally disillusioned, all of my expectations had failed me. I really had no idea what art was then. The idea I did have was very old fashioned and uninformed. The course in Waterford was quite radical. It had just changed from Fine Art to Applied Art, out with the old, in with the new! I was not ready for this challenge at eighteen. I went back to Gorey, and for the next three years I painted and explored what painting was, could and might be. I also made a living as a sign painter. The paintings I was making at that time were influenced by everything from Cezanne to Pollock and beyond. I ate, drank and slept painting.

I applied to NCAD in 1993 and was fortunate to get accepted. In the summer of ’93 I had my first solo exhibition in the upstairs room of a local pub. It was, and still is, important to me because local people started to support me and I sold most of the thirty paintings on show. Many of the people who bought these works still have them, and I often bump into them around the town and have chats about the work and what I am doing now, twenty-five years later.

Around this time I began to train in TaeKwon-Do. I went on to teach TaeKwonDo, and retired from it in 1999, which was when I began my MFA in painting. TaeKwon-Do gave me a great sense of focus and discipline, and the importance of sacrifice. I applied this to painting.

I began my four years of study at the National College of Art & Design in September 1993. This was a huge change in my life, trying to navigate living in Dublin and studying in a college where everyone seemed to know more than me. I threw myself into the Core Year with a determination to explore and learn as much as I could. I approached every task as if that's what I was going to specialise in. As the Core Year progressed it became obvious that painting was my natural inclination. I was making 8x10ft gloss paintings on sheets of card joined together. Most of the work I was making was inspired by landscape, but the material qualities of the paint was taking a prominent role. At the end of First Year I had an exhibition where I hung paintings on trees in a forest.

It was around this time that I started to see painting as a form of proposal or investigation. I was also immersed in art theory, and I began to think that the model that existed in contemporary painting no longer made sense. Contemporary painting flaunted with finding a “thing”, and doing it again and again, and this would be how to have a career. I struggled with this idea.

Second Year was when I entered the Fine Art Department to study painting. It was a bit strange in retrospect. The department was still trying to shake off academic approaches to painting. So there were still some rather strict approaches to teaching with regard to the human figure, life drawing and painting. I had discovered painters such as Albert Oehlen and Fiona Rae, who appeared exciting, as they were throwing the language of painting around in a way that seemed relevant. I produced a vast amount of work in Second Year and worked my way through a lot of different ideas and approaches to painting.

Third Year was a tough year. I spent a lot of time researching in the library and doubting painting. There were two very different teaching approaches: on one side I was told that I was a very accomplished painter who was doing very well; on the other side I was told that my work was far too derivative and that painting was a waste of time. I began Fourth Year with this baggage firmly attached to my thoughts and struggles. The one thing that I needed at this time was to have someone help me unpack what I was really about. There was too much discussion about how the paintings looked physical, but very little about the ideas that generated the work. I technically could do almost anything with paint but the Why? and the What? were not being given enough attention. Maybe I was too young and had not experienced enough in life to ask these questions in a serious way.

I graduated in 1997, making paintings that were influenced by Howard Hodgkin. The paintings were successful, and for a while I bought into the attention and hype, but I would soon become restless. For the academic year 1997-98, I studied for a HDip in art education and began teaching in September ’98. I was continuing to paint and teach and doubt. This doubt, at that time, was crucial, as it motivated me to apply for the MFA. The MFA is really what defined me as an artist. It didn’t start out like that, but it was a fantastic experience. I started the MFA with an attitude of exploration, not (at first) of painting, but of me.

I wanted to find out if I really had anything to say? And if I had something to say, I could then work out how to say it. It was at this time that I read an essay by Bridget Riley, ‘Painting Now’. In the essay she basically says that third level art education is the wrong way around; it teaches how to imitate the look of art. Ideas must come first, then the means of deciphering and translating the idea into an art work. This shocked me when I read it, because it was such a simple but common sense approach. I applied it to my MFA and quickly realised it was not as simple as it sounded, but it was the correct way to go about things.

The first year was very experimental and reflective. In fact, for the first time I spent more of my energy reading and thinking than making paintings. I was gradually becoming more disillusioned with painting. But I was determined to arrive at a conclusion: was painting still worth pursuing? And if it was, was there anything worthwhile to say? As I transitioned into Second Year I was convinced I would not be painting after the MFA. In fact, as the year went on, I was thinking I would not present work for the MFA, that I did not simply want a qualification, it was far more important to me than that. I was exhausted listening to all the theoretical discussions, all of which seemed plausible and worthy of consideration. I got to a point where something I had enjoyed since the age of ten was becoming a chore. The enjoyment had gone and all I was left with was the echoing sounds of numerous theories for and against painting.

I decided to concentrate all my energy in the making of six paintings, each measuring 12x12ins. If I could make them work they would become my MFA show. I was determined to make paintings that manipulated the physical qualities of paint based on ordinary, everyday emotions. I wasn’t sure if I was going to present work for the MFA show, and it was only the day before the work was to be examined that I brought my work to college and installed the six paintings. I was quietly pleased with the work. I had no idea of how those six tiny paintings would change my life and launch me on a path that has been full of opportunities.

My ideas about education have changed as I have progressed as an artist and a teacher.

The experience in NCAD for the seven years I was studying there was invaluable to me. However I have mixed views on third level art education (particularly from a painting perspective).

Over-teaching is a problem in my opinion; telling students what they should do, rather than, facilitating the discovery of what might be possible. This over-teaching leads to laziness, complacency and an imitation of art making. Of course, it is also possible that most art students are too young to make serious or substantial work at undergraduate level. The work I made for my MFA show was part of a wider conversation within contemporary painting at that time. It was connected to process painting, which was dominated by painters such as Jason Martin, Zebedee Jones, Alexis Harding, Callum Innes etc. I could probably have only developed this work within the environment of an art college, where the most current developments in painting were to the fore.

After I completed the MFA programme I was taken on by a commercial gallery. My work was taken to international art fairs and lots of other opportunities came along. I was constantly in the studio making work for art fairs and exhibitions in various different galleries in Europe and the USA. Everything I painted was sold; in fact it was often sold before it left the studio. I could have continued making that work and had a “successful” career. But I was far too restless to keep churning out the same work. In a very real way this was when my real education began. The changes at first were rather tentative and linear.

In 2009 I moved out of my studio to begin making work in my house. A couple of days before I moved out of the studio I had a huge desire to make a piece of work. I only had a piece of grey sugar paper, a pencil, a crayon and a few odds and ends of wood. I made a drawing on the sugar paper with pencil and crayon. I glued it to a piece of plywood, and cut four pieces of roughly one-inch wide cuts of timber to become a frame that I painted with acrylic paint and attached to the plywood mounted drawing. From this day forward I continued to develop work using a wide variety of materials. Oil paint was almost non-existent in my materials list. It was also at this time that I began to feel uneasy about my position as an artist and what was expected of me. The art world, career, attending openings etc., all started to feel uncomfortable for me. I was starting to believe that to make work without compromise I would need to step back from the machine that is the art world.

'Making Familiar' conversation with Mark Swords and Paul Doran (Right), 14th September, 2012, Temple Bar Gallery and Studios Dublin; curated by James Merrigan & Robert Armstrong

Around this time I started to think about a very old aunt of mine who lived in isolation in the countryside. She was many years deceased, but when I was in my late teens I would travel on my bike the ten or twelve miles journey to visit her in her very old cottage. I often carried a sketch pad with me, and would stop along the way to hurriedly jot down some lines that loosely resembled the terrain I traveled to get to the cottage. The drawings were more like a form of shorthand. I would often write words where certain things were. For example, instead of drawing a house I would write the word house in the place it was located in the general scheme of the drawing. When I arrived at the cottage, dozens of cats would scatter as I opened the creaky and rusty gate that once was painted red. Inside the cottage was dark and dusty with a stone floor. All around the interior on shelves, counters, tables and everywhere were all kinds of assemblages of food packaging and containers that were often joined together and painted and decorated. My aunt made these to occupy herself; she didn’t see them as art. At the time I didn’t see them as art either. But years later I long to be transported back to the cottage to view these fascinating assemblages. When I first encountered these assemblages I had never heard of Richard Tuttle or any artist that was using unconventional materials. Recollecting this experience had a huge impact on how I would proceed with making work from 2009 onwards. Living and making work in the same space was something that, at first, I was nervous about. Now, ten years later, I don’t think I could work anywhere else. It has given me a freedom that I don’t think I would have if I still had a studio separate from my house. I now tend to make whatever I want, using whatever materials I want. I don’t intentionally try to make paintings that are very different from each other. I just go with my curiosity. It makes no sense to me to stop myself doing certain things or to prioritise one way of making over another.

Thank you to Paul Doran.

Paul Doran is an artist who makes daily paintings. His paintings explore the possibilities of the material qualities of paint and how such materiality can communicate. The paintings are made in a matter of fact way, just as one might sweep the floor or shop for groceries. Doran believes in the integrity of the human hand as a means of a more fulfilling and sustaining mode of communication. He lives and paints in a small house beside a road, on the edge of a village. He lives with his paintings. His paintings grow and evolve out of his daily living and the paintings become a product of such an approach to life. Doran believes in the benefits of living with art. Of eating one’s meals with paintings not as mere decoration but as guests. In this manner one can have a continuous dialogue with art and grow with it, under its guidance.

THE DEEP—SEATED INTERVIEWS are composed & edited from textual correspondence between interviewer, James Merrigan, & selected artist interviewees. The interviews aim to interrogate the “depths” of art-making.

If you are interested in participating, email 5 images that represent your art-making, with a 100-word statement of interest. Artists will be selected for interview based on the possibility of an interesting & open discussion.