Mehitabel.

Mark Swords.

KK Dublin.

7.11.2018.

12.31PM.

Threatening rain.

✍🏼WRITING WHILE LISTENING TO TO THE RAIN🎧

Mehitabel.

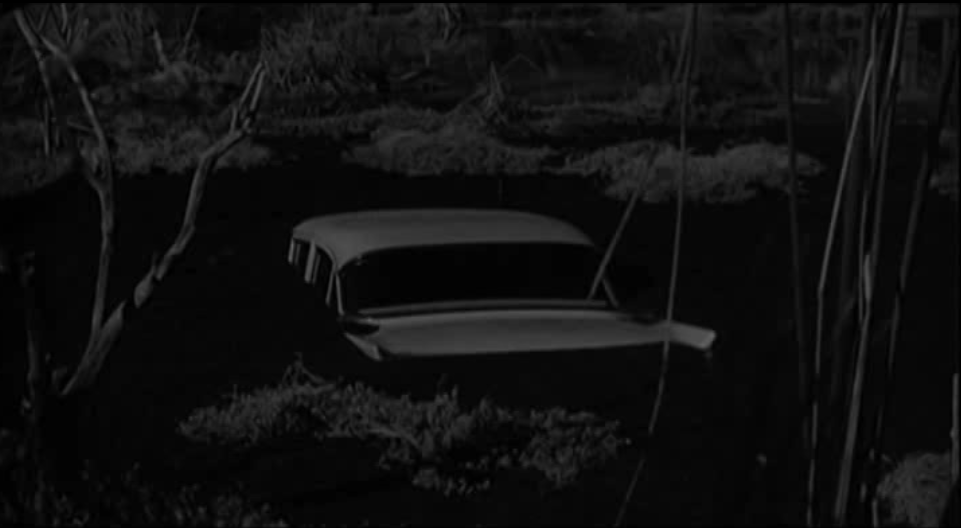

Gallery. Mark Swords. Five paintings. Colourful. Tatty. Big. Square. But that's where the easy descriptions end. First: their squareness? Somehow Mark Swords’ new paintings present as square at KK Gallery, although they do not measure square. Their size and form, headless and amputated like a Greek statue gone through the Time mill, intimates this perceived squareness—facing the midsection of you and me, shoulder to groin. They are paintings that face you when you make personal space, between you and them, a minimum. Up close we get snatches of raggedy cloth, uncanny buttons, failed tabula rasa, and squeezed-straight-from-the-tube paint…..waiting to be baked the rest of the way. Joyful abjection is being exchanged, up close. Across the empty gallery divide other visitors (students, I think) also butt shoulders and groins with them, spitting rainbows in the noon light as they awkwardly discuss their pros and cons. Mark Swords has always created formal arguments on the canvas by adding more stuff to his already screaming tablecloth. Nothing new there. And like before the cutlery and spilt-over world is still all over the place. Slovenly—a word I have come to depend on recently in terms of writing on painting, what one online dictionary defines anecdotally as “what your great Aunt Mehitabel might call you if you came to high tea without a necktie”—defines these well. In its stated messiness and civility, slovenly speculates on an originary tidiness, as if we all arrived clothed and clean at birth, not naked and decorated in blood and guts and shit. But I think we can do a lot better than Aunt Mehitabel in terms of painting. Slovenly onomatopoeically describes painting, like lips trying to mouth “Love” while kissing. Slovenly is the act of being physically close, too close, so close that words become physically entangled with the object. Lyrics become moans. Slovenly is being caught in the act, or trying to intellectualise a physical act that intellectually stutters, slobbers, spits rainbows: painting. Slovenly and smothering (words that carry words) navigate distance to achieve trust. Mark Swords’ paintings are best up close, in person, in the flesh. They lie from afar. They look dumb on your phone, a device that makes you manage art better but see and experience art less. Like the pregnant sisters S((love))nly and S((mother))ing, these new paintings carry sources and references mummified by the making and doing of painting. They’re crafty. Mark Swords cannot “unlearn” himself (he confesses in print here) but maybe he can unlearn materiality (if you think art making and artist are mutually exclusive…). The exclusive feminine metaphor ((pregnant)) is not lost on Mark Swords’ work as a whole (sewing and fatherhood). The artist has always worked outside the painted stretcher to transcend edge or border or thing or gender. Things hang and drape with their loose threads and associations releasing us from any sense of objectification (even with the red dots telling us different). Last year at TBG+S Mark Swords’ work exploded outward to range across the gallery, citrus and flat. We were confronted with excess, floor to ceiling, made by a rabid child, a rabid father. Here, these five compress that theatre and force a more intimate contact. Carnival chevrons come veiled in fudgie neutrals leaving traces of the clown and streamers from the kids’ party at TBG+S, like rainbows that signal the waltz of light and rain. Bonnard’s breakfast table, civilised and bespectacled. Mark Swords gives a transcendental flatness to the objects he makes, as if an object fully inclosed by an edge or a border or opacity would push the observer away to view from a far. These are up-close paintings, get-lost paintings. One painting here has a zip of stitching scaling the West edge, but nothing NE_S. These absences and resulting asymmetry gives the feeling of paintings being slung over stretchers or tables or whatever gives them their loose structural integrity. Mark Swords, an artist of many things, a collage artists, allows materials to collapse in on themselves through a social push and pull to relate everything to everything. What you get in his democracy is a density towards the centre, anchored by hat, pyramid, plant and so on. However the centre is under fire from the elements that helicopter on the skirted outskirts. This is where his paintings retain the vitality and integrity of the studio. Here, on the outskirts, things get jumbled and debris is allowed to form arabesques that are maze-like and pretty and open, as if a more austere and angular world once existed and now, after its ruination, collapse, flattening, razing, a new blossoming springs forth that is shadowless and endless under a pulsing sun. Pause. Pause. Pause. In the very confessional text that accompanies the exhibition Mark Swords admits (to himself) that he has got older. He has ((born))e a “son”. He is indeed himself “still” a son. He is not too old, he is not too young, he is in-between, in a space that doesn’t look forwards or backwards—the polarities of the age of man—but wanders and wallows at a centre of being, reflection and prophecy, somewhere on the highway towards the lost and found depot—The Lost Highway Guy. (…..horizonless-dark I hear the warble of music from the spaghetti-junction wilderness…..)

Through 24 November.