Painter, painter

Mairead O’hEocha

“Nothing seems more appropriate today than thinking community; nothing more necessary, demanded, and heralded by a situation that joins in a unique epochal knot the failure of all communisms with the misery of new individualisms.”

“...when this community dissolves, it leaves the impression that it could never have existed, even if it existed.”

“A fox knows many things, but a hedgehog knows one important thing.”

“It’s very tiny – very tiny, content.”

What is it to paint in a city? This is the question that has haunted and taunted me since Pallas Projects Dublin directors Mark Cullen and Gavin Murphy first invited me to write this essay that accompanies their selection of “Dublin City painters” for the Zagreb Biennial of Painting 2021. In its five previous editions the Zagreb Biennial of Painting has used the European city as a way to define and demarcate painting practice within a given national art scene. The participating artists’ somewhat loose connection with the city determines their selection. Pragmatic? Political? Economic? The reasons why the geographical parameter of the European city is being used to curate and locate European-wide painting practices within large if not always capital urban centres is beside the point of this text. However something can be philosophically gained from the identification and definition of painters and painting shepherded within a given city.

An exhibition of paintings displayed and displaced in a gallery in Zagreb, paintings by Irish artists born, bred, educated or active in Dublin City, will end up being defined in national terms rather than city-limit terms. City-limit terms make it a much more complicated and enticing proposition if we are to think beyond broad notions of gift-shop nationality, which includes Guinness and Leprechauns in our case. City-limit paintings could invoke the fantasy of an art scene that fosters and generates individual styles or schools of painting conceived in reaction or in resistance to other individual painters or groups of painters. From this localised perspective the Croatian observer might perceive what is playing out before them on these alien canvases as a symptom of artistic, social and political togetherness in a city far from theirs. The same observer might imagine what we will tentatively call a ‘community of artists’ working with and against each other, even though we know following failed communism via the post-war philosophies of Georges Bataille, Maurice Blanchot and Jean-Luc Nancy that community is unavowable and inoperative, especially today when faced with the “misery of new individualisms” that proliferate social media, our current existential crisis.

On first being invited to write this essay I wondered what was the criteria for the selection of painters who would represent Irish painting in the Zagreb Biennial of Painting. I looked down the list and recognised all 25 painters. It would be a lie to say that I appreciated all 25 painters listed in terms of formal innovation or critical ambition, the same way all 25 painters do not appreciate one another formally or critically (painters are especially harsh on their peers). What can be said is all 25 painters have attained varying visibility in the Dublin art scene. They represent different generations and art communities within the Dublin art scene, the Dublin city-limits being the invisible border used to curtail the curatorial process. As community is something I want to discuss in terms of painting practice within and without the city, I will first define what I mean by community in a painting context by first defining What a painter is, What a city is and What a community of influence is before approaching the primary question of this text What is it to paint in a city?

What is a Painter?

Eleanor McCaughey

In a time when it seems artists play multiple roles rather than a unit of activity, and when the weight of art history has been injected with helium, painter is a very different designation than artist. An artist is someone who is not defined by a medium but undefined via a way of being. Artists float above the media they pull from their quiver. The artist's idea or expression precedes and follows the medium so that content and form collide to form something new and undefined. The artist is metaphysical; the painter is defined by the object of paint and action of painting. Painters are stable but necessary glitches in the grand scheme of curated things, a schema where critical if not market value is placed on the transdisciplinary. Confronted with this unit of activity, one that is bound by an edge, a limit, but like a chessboard on which infinite moves lead toward an abstract endgame, the professional shape-shifters of culture find the painter an absurdity in a gene pool that values dynamism between media and human interlocutors. Painting may be the very thing that Oscar Wilde was thinking about when he defined art as the purest form of individualism.

If we go along with the line (no matter how absurd this line of thought may be) that being a painter is an absurdity in the postmodern and pan-aesthetic world of anything and everything goes, then the exclusive banner of “Painting Biennial” further compounds and expounds the idea that the painter remains a hedgehog in means but a fox in message, even though some if not most of the 25 painters representing painting within the cloudy city-limits of Dublin would rather be called an artist over a painter, a fox over a hedgehog. And yet some of these painters, not all, have made out-roads beyond the city-limits of the object and action of paint to spawn a type of sculptural excess that wanders beyond the paradigm of painting. But this excess is still determined and reeled in by the body of painting around which this excess orbits, and without which would slip away into space.

The curators here have selected 25 painters based on the self-determined and publicly affirmed value of painting in their painting practice. The two curators are not painters – this is significant. As non-painters they may have easily sided with painting practices that expand outward towards a spatial excess to the detriment and perhaps disintegration of the painted object. Beside taste, timing, vicinity and visibility, if two painters were invited to select 25 painters for the Zagreb Biennial they might – in a rhetorical sense – try to promote painting's playful agency beyond its delimiting edge by selecting some expansive painters. But painters, of all artists – if we can call them that here – value (or perhaps love is a better word) painting above all other mediums. A painter's painter is a real thing not a fantasy. Further, painters value other painters’ judgments and observations above curators or other agents in the art scene. To be recognised by a fellow painter is everything to the painter – as one painter said to me in an interview when asked about an audience for painting: “I paint for other painters!”

What is a city?

Colin Martin

The painter, as has been discussed, is determined by the medium of paint and doubly so by the curatorial context of a biennial of painting. But what of a city in terms of determining painting practice? Here, in this biennial, painting is not merely a decorative vista or filler against the focal point of a curatorially sound and socially aware serious art. No, painting is claiming a space for itself tout court in the absence of everything but the city (keeping in mind the city is a curatorial excuse, exercise or excess rather than a serious context to lump a selection of painters together in an exhibition).

That said, the city used as it is as a defining parameter is significant and somehow secure in itself – “regional painting practice” seems less critically relevant if indeed art is a product of the individual conditioned, determined and corrupted by society rather than something that lies deep and detached from society within the individual. Painting in relation to the city is less of a fantasy, less caught up in the idiosyncrasies of the individual outsider or misfit, and more in touch with the comings and goings of a world and its people and their politics, a society always on the move and always changing vis-a-vis the perspective of the transient painter who moves through the city, belonging and not belonging, alone and not alone.

Stephen Loughman

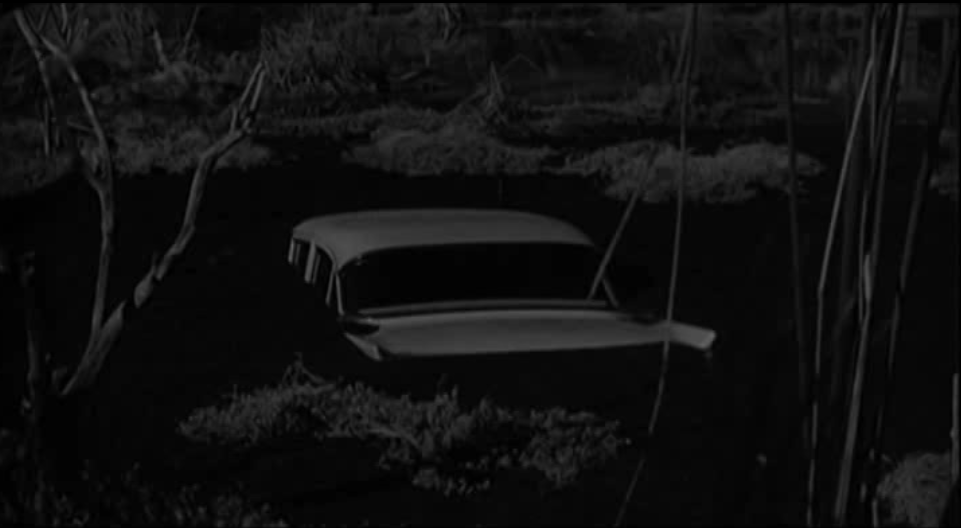

There is realism in the use of the city as a curatorial device, a realism connected with the hard institutions of ambition, audience, market and survival in the city, not the soft subjectivity that lies beyond the city-limits where the painter seems to disavow institutions while also ache for their attention. The city manifests less of itself and more of the fantasy that lies beyond the city-limits, a space without limits that drags up images of the outsider artist painting away to their heart's and obsession's content with a symbolism and mythology, naïve and original, but in keeping with the naïveté and originality of other outsider artists. Realism and fantasy get enmeshed where the city-limits meet their end, where the Lynchian highway drifts away into the darkness, where social agency is lost and individual self is gained, for the good or ill of the individual or painting.

Society – to the concentrated degree of the city – can be a corrupting influence on the individual as Jean-Jacques Rousseau maintained. If authenticity is a rejection or turning away from society and the other, then what is authenticity in terms of painting? The authentic painter is characterised by the outsider artist – individual, naïve, uneducated, unsophisticated but original in an outsider-artist-kind-of-way. The outsider artist is someone removed from society because they cannot help themselves from being corrupted by external influences. It is way too easy to be led astray beyond the city-limits into the romance and fantasy of the outsider painter. Whereas the painter who resides within the competitive and crowded city-limits resists such mythologies. The former, far from the madding crowd, fuses into something both real and fantastic, an authentic self realised in the symbiosis between being and painting.

What is a community of influence?

Oscar Fouz-Lopez

It is difficult to return from the fantastic hinterland beyond the city-limits to try to answer the primary question of this text What is it to paint in a city? A question we have splintered into three thorns: What is a painter? What is a city? and finally What is a community of influence?

The ideal of community is not just this writer's fantasy but the fantasy of every artist who has placed romantic or influential weight on schools or movements in painting from Leipzig to New York. Historical precedents also exist in philosophy during the Liberation in Paris when the efflorescence of the French philosophical avant-garde blossomed in the wake of the world wars in the war journalism of Albert Camus and existentialism of Jean-Paul Sartre. The idea of artists coming together in the art scene as lover-artists in the bars and cafés of the city is somehow a much better image of the artist than that of the isolated genius-artist reinventing the wheel on the foothills of creation without a community of influence. The influence of the other in real terms: on the ground, inside the studio, the gallery, the bars and cafés of the city, up close and in-person, must infiltrate the heart, head and paint of the painter. It must! The other proffers the artist permission to paint within and beyond themselves. The painter's community is a community of influence.

But this community of influence is not a public community. It's not the public community of the Hippie Generation that, through the coming together of public protest in body and spirit, proclaimed a community through love not war. Nor is it a community of the Occupy Movement that, as Jacques Rancière observes, populates and protests through an inactive body. The art community is coy. It is a bi-proxy community of influence that rubs up and against the other to stress the predilections of the individual artist. The painter borrows, begs and steals influence from the visible and recognised in the community. This community of influence plays out privately in the art scene, and those influences are subsumed beneath the painter's want and will to be different; not too different mind you, but different enough to be recognised as different but the same. A painting is recognised via the recognition of the other. However, the influence has to be almost unconscious or displaced for the recognition to manifest itself in the eye and memory of the community. Appropriation of and by predecessors and peers is a cultural phenomena that is both valued and rejected by cultural producers. Take for instance fashion designer Tom Ford's riposte to Miuccia Prada after she denied the influence of her predecessor :

“Mrs. Prada said in many interviews about the show that she had never been inspired by the work of her predecessor. ‘Well,’ Mr. Ford said, ‘Coco Chanel said that creativity is the art of concealing your sources.’”

The community of influence is there but not there, evident but veiled. Painting lives off a community of influence by both negating and eliciting influence. The community of influence is private*.

Oscar Fouz-Lopez

The community of influence in painting is nearly always a community of two. One precursor painter is the spine of the belated painter's practice – the spine being a useful metaphor to get across the formal structure that undergirds a painting practice, but also the spine (bravery) needed to break the same influential structure in order for the painter to make such influence their own. The individual painter sits in the driving seat carpooling influence, with the back seat full and the significant, influential other riding shotgun, whispering love letters in the ear.

“The community of the lovers [...] has as its essential aim the destruction of society. Wherever a temporary community arises between two beings, who are or are not made for each other, a war machine is constructed, or rather, the possibility of a disaster which, albeit only in infinitely small dosage, carries the threat of universal annihilation. ”

Love is the thing! From Blanchot we can equate love with the community of influence, a love that perpetuates the individuality of the painter, especially the ideal of the first love, that is if you have ever been subsumed by the love of and for another person. Not just the casual sort of love, love that is more of a demand for reciprocated affection or attention, or love that is spoken while looking at the world over the shoulder of the lover. No, the first love doesn't allow for the outside world, it lives off the fullness one feels in the presence of the other, and the negation of everything swirling around the other. The first love is shoulderless, intestinal, a monster with two backs. It's not attention-seeking or public. The first love crouches on the hands and knees, bends the spine, sucks face without coming up for fresh air. The first love stinks of itself and nothing else. The first love is one not two.

The community of influence wherein the painter becomes a lover and hater in their appropriation of the other painter is analogous with the brand spanking newness of the boy/girl, girl/girl, boy/boy relationship that turns its back on family, friends and society to become the monster with two backs. The healthy individual turns their back on the mirror unlike the sick narcissist who can’t turn away from their reflection. It is what Blanchot wrote following Bataille that interests me here in relation to painting and the city; painting being something private and digestive rather than public and productive. The community of two lovers (communities are always small) is something that hungers and lusts for love and all its spinoff emotions of hate, fear, vulnerability, lust, rage. We must not forget that painters hate their influences as much as they love them – painters are the best critics of their kind. They first embrace and then bury the community of influence to fashion an individualism that stands by itself, alone.

What is it to paint in a city?

Kathy Tynan (detail)

“Painter Painter” – the curated group exhibition of American and European painters at the Walker Art Centre in 2013 – is still my favourite exhibition title in any medium, and can help us to approach the question: What is it to paint in a city? But not for the reasons the curators titled the exhibition “Painter Painter”, which has something to do with the generative power of painting as a means rather than an end in and of itself. No, the reason “Painter Painter” still resonates eight years on from its inception in my brain is that it emphatically echoes what I have just discussed as the duality of the painter in terms of the community of influence and the lover-artist, but also the tautology that “Painter Painter” invokes as both an absurd repetition of the painter working within the limited parameter of the edge of the painting, and the narcissistic reflection of the painter trapped in their own reflection which ends up not being their reflection at all through the appropriation of the community of influence (in once sense painters bury themselves beneath their influence or at least side-by-side). The same repetition and tautology surfaces in American painter Willem de Kooning's words when he says painting has “very tiny – very tiny, content”. There is emphasis but also tautology – isn't one “very tiny” enough? Isn't one “Painter” enough? No, being a painter is always relative and in a sense, inauthentic. “Painter Painter” literally echoes this relativity. “Painter Painter” also proclaims itself, as if shouting like a manifesto. Painting is both private and public, narcissistic and generous, but firm in its need to be part of and apart from the community of influence.

What is it to paint in a city as opposed to outside the city ends up being a banal question. If we shorn the tail (“in a city”) from the question we are left with the head (“What is it to paint?”) . As this writer is a lapsed painter who painted for twenty-odd years inside and outside college, within and without the city, the question What is it to paint? is difficult to answer. If I were a writer looking and thinking from outside the act of painting like an object, like the farmer does at a city from the locus of the untouched landscape, I would have lots to say. But the subjectivity that drowns you in the act of painting blindfolds you from what it is to paint. To paint is beset by a mire of subjectivity. But if we look at what we are really asking via rather than vis-a-vis the question What is it to paint? we can see there is a manifesto-like quality – like “very tiny – very tiny” and “Painter Painter” – to the tone of the question (as there always has been with regards to the history of painting). As if to paint, since its inception as a form of manual labour in the service of worship, was always a product of the individual's imagination and desire to continue to resist the status quo of the democratic, which infers community and equality in the wake of the individual and liberty.

Within Dublin's city-limits, a city ribboned by grey motorways and greyer literature from James Joyce to Samuel Beckett, a city of words that circumscribe it like the knotted frames of the painted histories of other European cities, a city caught for so long in the infinite loop of religion, a city of brown canal deltas hemmed by green grass, white scum and rusted orange shopping trolleys, a city wherein the currents flow inwards against the politics that trickle outwards into the countryside where real power also resides and rests, a city that rains on the forget-me-nots and empty syringes that pinch the gaze on the boardwalks of the murky River Liffey, a city of painters that have always quarantined in their studios while looking sideways at the visible painters hosted by the gallery walls and minds of curators, a city where the painter is part of and apart from a community of public enemies and private friends, a city of promiscuous foxes desiring monogamy and hedgehogs desiring promiscuity…

—James Merrigan

Note

*Communities in the public realm are always making a statement about being a community. They are rhetorical communities, not real communities. Public communities are political whereas private communities don't need the public to sustain them, they feed off each other, like Bataille's destructive “community of lovers”. There is a self-sustenance playing out in the private community, one that feeds and sheds individuality. Whereas the public community that makes its publicness the thing is performing community for everyone else to see, to desire, to envy. The real community does not leave a trace, whereas the ideology or fantasy of community tries to impress one on the public. It is a lie.